As seen on WIS-TV, by Paul Rivera

For months, WIS has been investigating the effects of plastic waste on our Midlands waterways.

On Monday, we told you about a floating pile of trash that routinely collects at the start of the Columbia Canal, a source of our drinking water. The concern is that over time plastic breaks down, and then turns into potentially harmful microplastics or microscopic pieces of plastic.

In Part 1 of our WIS investigation, we collected samples of natural water and filtered to see how much if any material was slipping through the cracks.

Sarah Kell, a marine biology graduate student at the College of Charleston, helped us collect our samples. Part of her graduate research focuses on microplastics and how they affect us and the environment.

In total, we collected samples from 5 different natural water sites. One in the Columbia Canal, two along the Congaree, and two in Lake Murray. We then took tap water samples from 6 different locations like WIS-TV and the South Carolina Statehouse. We also analyzed 6 different brands of bottled water including Aquafina, Dasani, and Fiji Water.

Kell’s graduate program partners with the microplastics lab at The Citadel military college, which is where she met Dr. John Weinstein, the chairman of the biology department.

Sarah Kell, a Marine Biology graduate student at the College of Charleston, helped us collect our samples. Part of her graduate research focuses on microplastics and how they affect us and the environment.

Sarah Kell, a Marine Biology graduate student at the College of Charleston, helped us collect our samples. Part of her graduate research focuses on microplastics and how they affect us and the environment.

“What we found in our research is that these items break down a whole lot faster than people probably think,” Weinstein said.

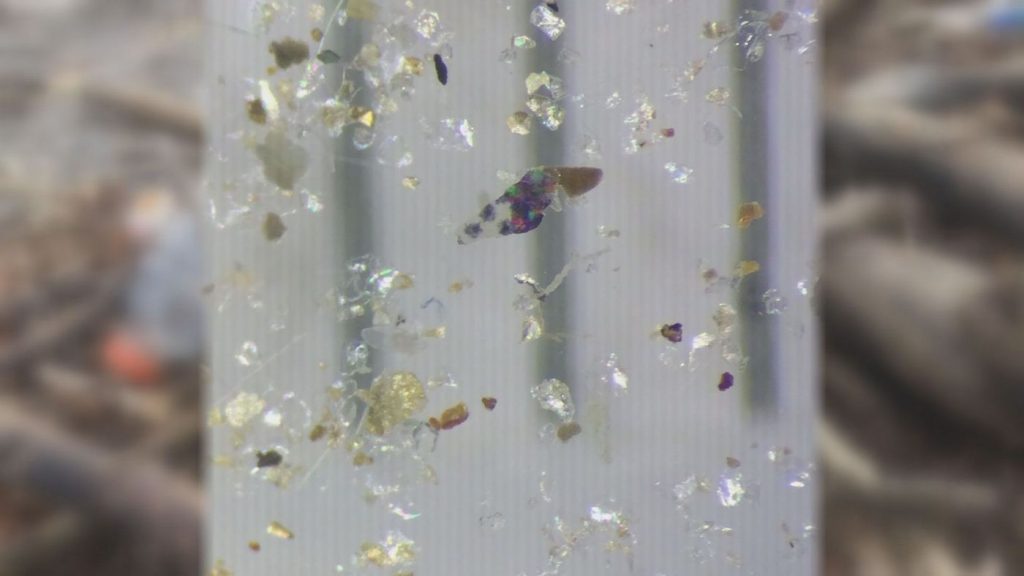

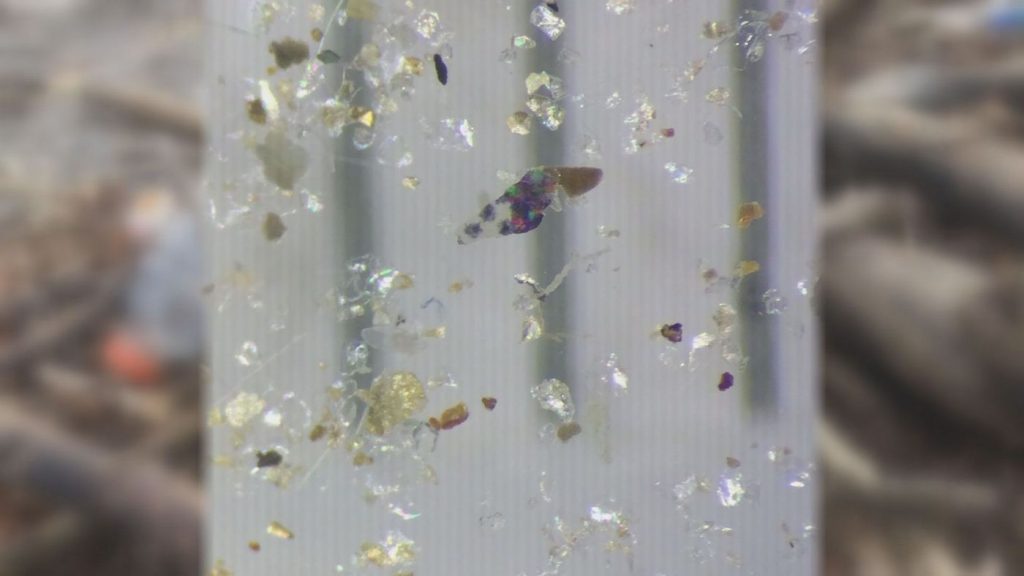

Once in Weinstein’s lab, Kell got to work, showing us how she combs through the water sample.

“I will place them into a dish in order to analyze the sample to look for microplastics,” Kell said.

Kell and her team found microplastics in all of our river and lake samples. Here is what we found in our natural water samples.

Different colored fragments, broken down from larger plastics were found in 100 percent of the samples. Microbeads, which were used in cosmetics and facewash, but have since been banned in the United States were found in 60 percent of the samples.

Fibers, likely from clothes, both man-made and natural were found in all of the samples. The fibers come from several different sources: washing machine drainage, drier machine venting, and normal shedding.

Foam from items like Styrofoam was also found in all of the samples.

The most abundant types of microplastics, however, came from tires. As tires break down, they leave particles on roads which wash into our water supplies when it rains. Weinstein’s research found these tire wear particles in Charleston Harbor as well.

Our experts expected to find a lot of particles in the river and lake samples, but what about filtered water?

Every single tap water sample contained microplastics (fibers, fragments, and one tire wear particle) were among the particles.

“At the capital is where we found the three fragments and one fiber,” Kell said. Even the legislators whose work could address this in the future, are drinking plastic.

The more promising news is that Kell and her team only found one and a half microplastics per liter in the most contaminated tap water sample. Compared to the highest natural sample, which came out to a whopping 90 microplastics per liter.

After analyzing the results, it is clear that our water filtration process cleans out a lot of the contaminants, but we wanted to know why that number isn’t zero. We took our findings to Columbia Water and spoke with Clint Shealy, the assistant city manager, for Columbia Water.

Shealy says our WIS investigation, is the first study he has seen being done on microplastics in Columbia. We then asked how are the microplastics getting through our filtration systems?

“What we use is not a straining process if you will, that would remove every particulate from the water,” Shealy said.

Shealy says the system is designed to take care of anything that is a health concern. He says more studies would have to be done on the health risks of microplastics before the city would invest in a tighter filtration system.

“Unless there’s a known health risk, generally, utilities and the drinking water industry don’t strain the water, or filter the water down to that level if there’s no known health risk because those processes are very cost prohibitive.”

Columbia is not the only city facing this problem. One study found microscopic plastic fibers in more than 94 percent of United States Tap water.

What we know now, is that microplastics can kill marine life.

While the full effects of microplastics on the human body are still being researched, we do know the health risks that the chemicals inside plastics could pose for humans. We spoke with Dr. Dana Nairn, who works at Providence Health in Columbia, she broke down some potential health risks.

“Diabetes, there are issues with weight gain, it affects the thyroid gland. Decreased fertility in both males and females,” Nairn adds, “The autism spectrum disorders.”

However, for the purposes of the WIS investigation, Shealy and our experts say there have not been enough studies to show the health risks of microplastics so that is why people like Kell are doing the work they are doing.

One more thing, if you thought about playing it safe and drinking bottled water, instead of tap water, well we have bad news for you, the study found on average more potential microplastics in plastic bottled water, than tap water.

Larger studies have been done on the microplastics found in bottled water where 93 percent of samples found microplastics.

Since we don’t know enough about these microplastics, we are diving a little deeper into the health risks caused by plastics with our experts Wednesday on WIS.

Dr. Triz Smith, ’98, appointed by SC Governor to The Citadel Board of Visitors

Dr. Triz Smith, ’98, appointed by SC Governor to The Citadel Board of Visitors Top takeaways from the National Collegiate Honors Council conference

Top takeaways from the National Collegiate Honors Council conference A new kind of Frankenstein: bringing cadavers back to life in the classroom

A new kind of Frankenstein: bringing cadavers back to life in the classroom