As seen in Stars and Stripes, by Rose Thayer

Examples of an expanding cyber force within the Defense Department are all around. The Marine Corps established a new specialty field in October to better defend its computer-based systems and the Air Force added 244 new cyber officers in 2018, a nearly 10 percent increase from the previous year.

Increasingly, the military services are focusing on cybersecurity, in part based on information from the Department of Homeland Security citing the potential of a cyberattack exceeding the threat of a physical one.

More so, an internal Pentagon report recently obtained by Bloomberg News detailed the need for a larger, more competent workforce — among other suggestions — as concerns of cyberattacks percolate throughout the U.S. military. The internal report from the Pentagon’s combat testing office warned while the military has made progress in defending against in-house attacks designed to test cyber systems, the improvements were not outpacing the growing capabilities of potential adversaries.

To better prepare for the growing cyber threat, the military needs a workforce capable of preventing, detecting and mitigating attacks, Robert Behler, the Defense Department’s director of operational test and evaluation, wrote in the report. While it can be challenging to draw competent workers from higher-paying private sector jobs, he suggested the Pentagon increase its employment by better funding the college-to-career pipeline.

The Pentagon should provide funding for a select group of military service academies, private companies, universities and national laboratories “to grow the DoD’s cybersecurity testing workforce and capabilities” while developing automated tools because “hiring more cyber experts will not be enough,” Behler said.

The groundwork for this recommendation is already in place. The 2019 National Defense Authorization Act outlines the Pentagon’s intentions to carry out a cyber education program at any university’s ROTC program “for purposes of accelerating and focusing the development of foundational expertise in critical cyber operational skills.”

The law goes on to prioritize programs at the nation’s six senior military colleges because of their large foothold in commissioning officers. Together, these schools commission about 900 military officers each year – about 12 percent of annual ROTC commissions.

The University of North Georgia, Texas A&M University, The Citadel, Virginia Tech, Virginia Military Institute and Norwich University make up the nation’s six senior military colleges, as designated by meeting specific requirements of the Title 10 U.S. Code in their ROTC programs.

Working together for funding

Together, these universities are lobbying for further support and funding – primarily to expand their offerings and create more scholarships for students.

“Our intent was to work with the Department of Defense, so they could help us take that next step,” said retired Col. Sharon Hamilton, director of liaison and military operations at the University of North Georgia’s Institute for Leadership and Strategic Studies.

Five of the six senior military colleges already have cyber programs with aligned curriculum as recognition of academic excellence by the National Security Agency. The allocation requires they meet very specific criteria and include certain areas in curriculum such as cryptology, network defense and cyber security principals. It also makes students eligible to apply for scholarships, internships, and grants through the Defense Department.

Scott Stewart, vice president of tactical analysis with Stratfor, a private, intelligence firm based in Austin, Texas, said the idea of turning to colleges is a logical step in the process of increasing personnel and improving cyber security.

“The entire universe for cyber has gotten so large, both offensively and defensively, it makes perfect sense to have to get servicemembers who understand this realm and to have the technical proficiency necessary to be effective in a cyber battle,” Stewart said. “There’s been some awareness over the last couple decades, but really within the last five to seven years we’ve seen everybody really realizing it. Not just at the military level, but if you see the statements coming out of Congress and other branches of the government for the need of the U.S. to have this capability and to beef up the DoD’s capability in this area.”

Stewart mentioned the Equifax breach that exposed the sensitive information of 143 million Americans in 2017 combined with the 21.5 million records stolen from the Office of Personnel Management two years prior as a potential way for enemies to use cyberattacks to ferret out the names of intelligence officers.

Other types of threats include shutting down public utilities, attacking financial institutions or compromising democracy by hacking voting systems. They can come from adversaries such as Russia, China and North Korea, cyber criminals, activists and terrorist organizations, said retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Jim Keffler, director of cyber at Lockheed Martin Government Affairs, which manages the company’s U.S. government customer relationships and develops policy, regulatory and legislative strategies with Congress for all Lockheed Martin programs, products and services.

“Ten years ago, there was only a handful of nation states that could do cyberattacks — you could probably count them on one hand,” he said. “As of last year, that number had grown to over 30. That threat keeps increasing.”

This is what the U.S. government is primarily concerned with, he added, including the Defense Department.

“The goal for DoD now is to build capabilities and to build cyber operations to increase lethality and effectiveness of the force,” Keffler said. “And in order to do that they need a workforce to build out those skillsets and so we go back full circle to those things that need to be done to grow the workforce toward military career and initial assignments.”

Students studying cyber curriculum get an interdisciplinary education that can include the study of strategic foreign languages, cyber security engineering, policy, management, cyber security law and computer science.

The universities and the Defense Department see this plan as a way to generate more cyber experts ready to fill jobs with high security clearances at military and government organizations.

Hamilton envisions new funding to support scholarships that commit students to work a couple years with Defense Department entities — perhaps even finalizing their security clearance before graduation so they can go straight to work.

“Once you show someone and you introduce them to your culture, if its good fit, they’re going to stay,” she said.

Expanding Cyber Operations

The Defense Department’s cyber community has about 6,200 people, when including personnel from U.S. Cyber Command, the individual services and the Cyber Mission Force, which directs and coordinates cyberspace operations, according to information provided by Cyber Command.

Each military branch also has its own variation of cyber commands and operations. Within the Marines, cyber-specific officers are new to the playing field.

The branch launched their cyber occupational specialty in October and now has more than 100 cyberspace operation officers, said Capt. Joseph Butterfield, a spokesman with Marine Corps. The occupational field consists of officers who laterally moved from a previous occupation. The Marine Corps plans to designate 10 newly commissioned cyber officers each fiscal year.

The first two officers directly designated as cyberspace graduated from basic officer training in December and are now training for their specialty field, Butterfield said. These cyber Marines have the technical expertise to design defenses and protect digital information systems.

Meanwhile, the Air Force’s cyber operation began formally in 2009 with the creation of the 24th Air Force, now known as the Air Forces Cyber. It’s home to about 600 officers – 244 of whom joined the force in 2018, said Capt. Lauren Woods, spokeswoman for Air Forces Cyber. That’s up from 223 the previous year.

“The cyber mission is constantly evolving in both scope and complexity, which makes our trained and disciplined cyber work force more invaluable than ever,” Woods said. “For example, in May of 2018, Air Forces Cyber finalized its build of 39 Cyber Mission Force teams, a process that began in 2013 and will continue to evolve since reaching full operational capability.”

Educating Future Leaders

Developing leaders is where the senior military college officials believe they can help.

Five of the six universities offer a minor in cyber security, two have a bachelor’s degrees and two have graduate-level certificates. Together, they are planning to go to Congress and ask for funding to accompany the cyber institute guidance outlined in the NDAA.

“We can leverage things already in place and focus on interdisciplinary skills. Cyber is wonderful, but we want to build some interdisciplinary skills. We’re not only producing great cyber graduates but developing great cyber leaders,” said Hamilton of North Georgia.

The leadership foundation of an ROTC program is what sets their programs apart from other universities, said Carl Jensen, interim leader of the Department of Intelligence and Security Studies at The Citadel.

Agencies such as the FBI and CIA “like our graduates not just because of their academic skills, but also because of the focus on ethical leadership, loyalty and modesty. All the sort of things The Citadel tries to instill in graduates is exactly the sort of person who the public and private intelligence companies and defense contractors want to hire,” he said.

In 2016, 13 graduating seniors from The Citadel’s program were hired by the FBI straight out of college, Jensen said. In fall 2018, 104 freshmen at The Citadel declared intelligence and homeland security as their major. The Department of Intelligence and Security Studies, which houses the major, was launched in the fall.

Additional funding would expand student opportunities beyond the classroom, allowing for more cyber competitions, off-campus trips, expanding facilities and bringing more speakers and professional development.

“The competitions are a big deal,” said retired Col. Daniel Ragsdale, director of the Texas A&M Cybersecurity Center and professor of practice in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering. “It’s not a take a multiple-choice test and get a certification. In a competition, it’s hands on and you have to demonstrate your wherewithal.”

“We don’t want students to just come to class,” he said. “We want them to go to events, have employment opportunities, internships and extracurricular outlets for their interests.”

Cyber programs at A&M began in the 1990s and have grown to accommodate about 650 students. A minor launched in 2016 is now one of the largest in the engineering department, Ragsdale said.

“[Students] have beaten down the doors. The demand is off the charts,” he said.

In the past three years, Texas A&M has received more than $5 million in grants from the National Science Foundation and the Defense Department for scholarships to award to more than 50 students for the pursuit of studies in cyber security. Eight scholarship recipients have already completed their studies, 13 scholarship recipients are enrolled, and 30 scholarships are available in subsequent years.

Next year, The Citadel plans to renovate a space to house a cyber-intelligence suite designed to look and feel like the operations centers at the FBI and CIA. The space will include a cyber range and a cyber lab with dedicated software to work cyber security problems. Jensen said they are also seeking sponsorship to build a sealed room to work classified material, known as a sensitive compartmented information facility, or SCIF. This would allow students and faculty with a security clearance to work on classified government projects.

“If you look at the population of students coming in, they want to find programs that are intellectually challenging and academically rigorous, but at the same time, prepare them for skills to go out in the job market and be successful with that,” Jensen said. “In addition to the academic preparation and high-level analysis courses we teach, we’re also giving students skills to succeed out there in the real world and have marketable skills that employers are looking for.”

thayer.rose@stripes.com

Twitter: @Rose_Lori

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair

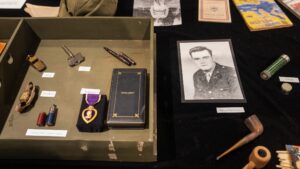

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day

The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day