As seen in the Marine Corps Gazette, by The Citadel Commandant of Cadets Col. Thomas Gordon, USMC (Ret.), ’91

So how does one acquire the consistency of character that will make it impossible for another to do them harm? The ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, particularly the Stoics, believed the answer lay in a proper education. The key to character development, they advocated, was a balanced education, grounded in philosophy yet practical in application. My book, Marine Maxims Turning Leadership Principles into Practice, is all about turning such principles into practice. At The Citadel, my job is to educate and develop principled leaders and return young men and women of virtue and character back to society where they can be successful in all walks of life. Here we focus on four character-developing steps that enable future leaders to build a spiritual parapet and shore up their emotional resolve. These four maxims have enabled leaders to persevere regardless of their circumstances for over two millenniums. They are:

- Discover and never forget your why.

- Do hard things.

- Control the controllable.

- Make it a habit.

Each of these maxims is a choice that cannot be imposed but only embraced. Xenophon was a Greek general and a student of Socrates. In his work, Memorabilia, he shares the legend of Hercules at the crossroads. This ancient Greek parable finds a young Hercules confronted with a choice between following a beautiful goddess named Voluptas who offered to fulfill his every desire or a stern goddess in a white robe named Virtue who promised honor and satisfaction only achievable through hardship and sacrifice. Aristotle incorporates this judgment in his definition of character. Character, he professed, is discovered in the pursuit of virtue and the avoidance of vice.

Personally, I subscribe to this classical definition — your character is defined by your personal choices. It is built by your inner confrontations and takes form in the struggle to overcome internal weakness in the pursuit of excellence. These choices, repeated over time, become habits — an engraved set of dispositions and a desire to do the right thing.

#1: Discover and Never Forget Your Why

If you want to be the architect of your character, you first need to know what you are building. Who do you want to be? A Navy chaplain friend of mine, Madison Carter, professed: “If you don’t know who you are, someone will tell you who you are. If they can tell you who you are, they can define who you are. If they can define who you are, then they can confine who you are.” Kevin Kelly, the Editor for Wired Magazine, wrote, “You complete your mission in life when you figure out what your mission in life is. Your purpose is to discover your purpose.” This is not a paradox. This is the way.

After the Bible, the most impactful book I ever read was Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl, a Holocaust survivor and psychologist, learned his answer to the preeminent question in a Nazi concentration camp when he discovered he was asking the wrong questions. “It is not what do I want from life,” he discovered, “it’s what does this life want from me? Where do my talents and gladness meet the world’s needs?” Frankl concluded that “what man needs is not a tension-less state but rather a striving struggle for a worthwhile goal.”

The first maxim in my book is “Know Thyself.” Why is it first? I write, because “when you know who you are, you will know what to do. Knowing yourself enables you to align your beliefs and your behavior. This alignment produces authenticity. See, the best leaders are acutely self-aware. They are capable of being honest with themselves about themselves. They know their capabilities and limitations and understand how each are perceived.” This degree of introspection can take decades to develop. Knowing yourself is hard! This has much to do with how we mentor junior leaders. We tell them to “be yourself.” Personally, I cannot think of any more hollow rhetoric to share with an aspiring leader. At eighteen, you have no idea who you are and that is OK. You are still figuring it out. So here is my advice: desire what you admire. Who are your heroes? Make a list of the people you admire and then use their examples to map your values. British economist, Alfred Whitehead, wrote, “A moral education is impossible without the habitual visions of greatness.” The moral failures that surround us today are not due to personal weakness, rather it is the result of an inadequate example. Find yourself a hero worth emulating.

In his book, Designing the Mind: The Principles of Psychitecture, Ryan Bush describes the “great tourist trap of life.” Here, he explains that the things valued by our society are not necessarily good deals. Our culture is acutely goal-oriented but rarely focuses on the right things. Success, as defined by popular culture and social media, has little to do with character and, ironically, happiness. Our culture confuses fame and popularity with success. When you aspire for something that is material, reliant on external events, or based upon the opinions of others (all of which are outside of your control), you will be left anxious, empty, and wanting more even if you achieve your goal. However, if your goals are internal and can never be completely finished or achieved, you will discover the satisfaction that can only be found in pursuing a life of significance and character.

If you need help defining who you want to be, the best guide I found is in Stephen Covey’s classic: 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Covey simply asks, what do you want people to say about you at your funeral? Most find this exercise strips away unessential material and thereby discovers the attributes of the person of character you aspire to be.

#2: Do Hard Things

I began by defining character as a choice. If you want to build an inner citadel of character, then choose to do hard things — challenge yourself. Doing hard things when you are young is a life hack; it literally rewires your brain. The science of neuroplasticity is a field of psychology dedicated to exploring how life experiences modify the software in your mind. Doing hard things in your youth develops coping techniques; a form of spiritual Jiu-Jitsu that enables you to redirect a blow and control your response regardless of the circumstances. Becoming comfortable with discomfort is the first step to mental wellness.

As the country emerges from twenty years of war, the focus has been on veterans’ mental health and post-traumatic stress disorder, but very little has been written about post-traumatic growth. Here the classics can be very useful. Seneca the Younger was a Roman Stoic philosopher in first-century Rome. In his letters, he professed that “true character cannot be revealed without adversity.” Whether you are quoting Seneca or Ecclesiasticus, “just as gold is tried by fire, man is by the furnace of adversity.” The truth is we in the profession of arms have shared a degree of misery the protected will never know. However, we also know that suffering is where goodness comes from. Suffering builds commitment; suffering builds character.

I tell the cadets at The Citadel before any rigorous training event that growth and comfort can never coexist. Getting out of your comfort zone and challenging yourself is how you build character. Every time a young person overcomes adversity, they build resiliency. Every time a young person successfully navigates an obstacle, they build resolve. The word resilience comes from the Latin verb resilire, which means “to jump back.” In science, resilience is the ability of a substance to absorb energy when it is deformed, and then release the energy back. See, resilience is not invincibility, but rather adaptability.

#3: Control the Controllable

One of my personal heroes, ADM James Bond Stockdale, Medal of Honor recipient and former President of The Citadel wrote, “The invincible man is he who cannot be dismayed by any happenings outside of his control.” The Admiral was actually paraphrasing Epictetus. Epictetus was a Stoic sage and a slave in ancient Rome under the reign of Nero. Stockdale was given a copy of his teachings, The Enchiridion (or Handbook), as a graduate student at Stanford. The ability to determine what is in your power and what is not is a tenet of Stoicism. In philosophy, this is referred to as the dichotomy of control. In psychiatry, clinicians call it subjective consciousness, or the ability to distinguish what is within your agency to control. The Serenity Prayer is a religious appeal for subjective consciousness.

I tell every freshman at The Citadel that there are only four things they can control during their “Knob” (Plebe) year. They are:

- Your preparation

- Your effort

- Your attitude

- Your response

Everything else in this world is out- side of their control. The truth is that these are the only four things we retain agency over in life. The reason why there is so much depression and anxiety in the world today is because people are trying to control things that are outside of their control.

Remember Victor Frankl? The Nazis stripped him of literally everything, yet he retained agency over his response. After the war, Frankl published his experience and his psychological theory: Logotherapy. Logotherapy teaches the practitioner how to reframe their circumstances to maintain personal agency. When you reframe your circumstance, you restore your perspective. It is when we forget our ability to choose, we learn to be helpless. You may not be able to control the situation, but Dr. Frankl would insist that you can always control your reaction.

#4: Make it Habit

Finally, character development is not a goal, it is a system. Consistency here is a superpower. I began by defining character as a choice, repeated over time until it became a habit. Our habits, therefore, reflect our character. Aristotle wrote “We are the sum of our actions, and therefore our habits make all the difference.” Habits enable our brains to be more efficient. They free our minds for creative and critical thinking while turning rote and repetitive functions over the autonomous portion of the brain. Every habit has three elements: a cue, a routine, and a reward. The cue is a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode. The routine is the behavior itself, which can be a physical act, a mental task, or an emotional response. Finally, the reward helps our brain figure out if its particular habit is worth remembering in the future. Our habits are also a product of our environment. Maxim #18 in my book holds, “People do what people see.” In his best-selling book, Atomic Habits, author James Clear writes, “We imitate the habits of the close, the many, and the powerful.” So, if you want to emulate the habits of those of upstanding character you must focus on the cues that make up your surroundings. The law of exposure holds that the mind absorbs and reflects what it is exposed to the most. We all learned in health class that you are what you eat. Well, what you put into your mind controls your thoughts. Cable news, smartphones, and TikTok do not create new motivation but instead latch on to the darker side of human nature. The Stoics profess that your life is moving towards your strongest thoughts: Where the head goes the body follows — perception proceeds action — right action follows right perspective.

A popular parenting refrain in my house was, “Show me your friends and I will show you your future.” Epictetus wrote, “Keep company only with people who lift you, whose presence calls forth your best.” The Apostle Paul was blunt: “Bad company corrupts good character.” When it comes to character development, the Stoics recognized that none of us are self-sufficient. We cannot do it alone. The fourth-class system at The Citadel and the Marine Corps’ Basic Training focus on building collective grit. In her book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, Angela Duck-worth discusses at length the power of conformity and the value of a “gritty culture.” Duckworth concludes that there are two ways to grow resilience, or what she calls “grit.” The hard way is to develop it by yourself. The easy way is to surround yourself with a culture of grit.

Conclusion

It has been said that when you have character that is all that matters, and when you do not have character that is all that matters. Maxim #44 in my book declares that talent can get you to the top but only character will keep you there. At some point, your character will be tested.

Combat is the ultimate arbiter of character. A leader’s character and the core values they imprinted upon their unit will be revealed when exposed to continuous contact. Lord Moran, Churchill’s friend and physician in World War II, argued that character must be developed before the trials of combat or its dearth will be magnified. In his book, The Anatomy of Courage, he wrote:

“Character is a habit, the daily choice of right instead of wrong; it is a moral quality that grows to maturity in peace and is not suddenly developed on the outbreak of war. For war, despite much that we have heard to the contrary, has no power to transform, it merely exaggerates the good and evil that are in us, till it is plain for all to read; it cannot change, it exposes. Man’s fate in battle is worked out before war begins.”

If you want the consistency of character that will make it impossible for others to do you harm, choose your struggle. If you want to do great things in life, choose to bear discomfort. Your mind’s immune system is much like your body’s: both require stressors and challenges to learn, adapt, and grow. There are few callings that demand more of one’s character than the profession of arms. If you aspire to serve and lead in defense of this great Nation, the Stoics can help you find your purpose and endure war’s cruel deprivation. The Classics teach us that everything worthwhile in life is achieved by overcoming difficult experiences. Modern society con- fuses a life of comfort and ease with the good life. The truth is the avoidance of suffering leads to more suffering. The good life is found in striving for excellence, getting out of your comfort zone, and incrementally overcoming your weaknesses by developing constructive habits. Controlling the controllable and reframing your circumstances is not suppression, repression, or denial but emotional self-regulation borrowed from Ancient Greeks. Your character emerges out of your habits, and your habits are developed in response to your environment. The Stoics’ notion of affiliation is key to the development of individual character and resilience. None of us are capable of doing this alone. We need heroes to emulate, leaders and mentors to push us beyond our perceived limits while keeping us on azimuth, and communities of cooperation, respect, and support to lift us up. When you know your why, have been put to the test, found a way to retain agency and repeat it to the point that it becomes a habit you will become that person of character impervious to attack.

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair

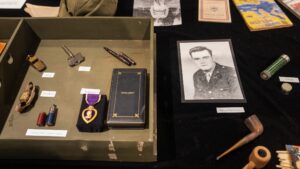

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day

The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day