Photo: Tire particles in shrimp GI tract

As seen on ABC News 4, by Caroline Balchunas

From bags to bottles, cars and clothing, plastic is truly the fabric of our lives.

Most people see some form of plastic pollution every day like water bottles or single-use straws, but it’s the plastic we don’t see that’s a larger concern.

About five years ago, researchers at the Citadel and College of Charleston began looking into microplastics around the Charleston Harbor and made a new discovery.

Dr. John Weinstein, biology professor and head of the biology department at the Citadel, leads the research.

Weinstein said from that study, they found two interesting things.

“We found Daniel Island had some of the highest levels that were being reported and we were also finding that the majority of the particles that were being reported were black particles,” said Weinstein. “We did chemistry on them and we found that they are composed of carbon-black and polybutadiene which are charred components of tires.”

Weinstein said the black specks were tire particles, another form of microplastic. Weinstein said it was an unexpected discovery, but not exactly surprising.

“When you think about tires and what happens to tires over the course of their lifetime, the tread on a tire will wear down,” he said. “But you don’t see 2,000 tons on the side of the road, right? So, where is it going?”

Weinstein said storm water runoff is likely to blame, washing the particles from the roadway to the waterway.

College of Charleston graduate student Sarah Kell studies the potential pathways and the role stormwater detention ponds may play.

“One of the questions we’re trying to look for is if there’s higher concentrations at the point where they’re flowing into the tidal creeks and any kind of impacts they could have on the environment there,” Kell said. “I hypothesized that storm water ponds would serve as a sink for microplastics because storm water ponds are designed to trap and filter pollutants.”

In the 900 samples she’s collected over the years, Kell said every single one contains microplastics.

“I’m finding all types of microplastics, I’m finding tire particles, different types of fibers, fragments as well as microbeads,” she said.

Weinstein believes there’s likely an engineering solution, but until a tire is invented that doesn’t wear down, he feels the most viable current solution is to control where the runoff goes.

The tire manufacturing industry is aware.

In a statement, the U.S. Tire Manufacturers Association said:

The USTMA cares deeply about the impact of tires on the environment. In 2005, USTMA members formed the Tire Industry Project (TIP) organized under the World Business Council on Sustainable Development (WBCSD). TIP works to proactively identify and address potential environmental impacts associated with the life cycle of tires to contribute to a more sustainable future.”

USTMA provided a study that concluded “tire road wear particles” are unlikely to have adverse effects on freshwater and sediment-dwelling species.

Weinstein said there’s a growing body of evidence that points to the contrary. He said a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences has funded a grant for them to study the potential impacts on human health and added the new findings will be published sometime this fall.

“These particles may be getting into our seafood, like shrimp and oysters,” Weinstein said. “There are chemicals associated with these tire particles, there are heavy metals and there’s hydrocarbons that could potentially be leaching out of the particles as they pass through the gut of the shrimp.”

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair

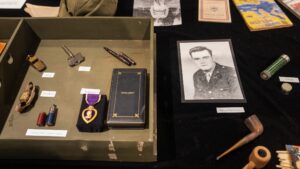

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day

The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day