As seen on Smithsonian.com, by Dr. David Preston, Westvaco Professor of National Security Studies at The Citadel, and award-winning historian of Braddock’s Defeat; Photographs by Allison Shelley

On the night of May 27, 1754, Lt. Col. George Washington led a party of Virginia soldiers out of an encampment in the Ohio Valley. The conditions were horrid—a night “as black as pitch,” as the young commander recorded in his journal. An unceasing rain made the dark woods even more impervious to the soldiers and warriors.

Washington was only 22 years old, his mouth still full of teeth. The uniform he wore was likely a woolen officer’s coat showing his allegiance to the British empire—he was a loyal subject of King George II. He and his Virginia Regiment of a little over 100 effective soldiers were the tip of His Majesty’s spear in North America. Their assignment: to finish building a fort that would anchor Britain’s control over the Ohio Valley.

But as Washington and his men marched westward over the Appalachian Mountains, they received stunning news: The French had already captured their intended destination, known as Trent’s Fort. Hundreds of French troops had aimed over a dozen cannons at the British soldiers stationed there and forced their surrender.

By May 24, Washington had encamped at the Great Meadows, one of the few open clearings amid the dark Appalachian woods. There he received word from a man named Tanaghrisson, an Ohio Iroquois, that an army of French soldiers was coming to attack his men. French tracks were spotted only five miles from the camp, and Washington sent out 75 of his best soldiers to search for the French party. Then his Indian allies found the spot where the French were camping, hidden in a glen near the crest of a mountain ridge.

On May 27, the men who remained with Washington—a small party of 40 British soldiers and perhaps seven or eight Ohio Iroquois allies—marched five miles and climbed 700 feet up the steep eastern face of Chestnut Ridge. Seven soldiers got lost as they stumbled in the rain over the ridgeline’s many rocks, spurs and draws. By the time the remaining 33 men crested the ridge, they were exhausted and soaked.

As the sun began to rise, the soldiers struggled to operate their muskets amid the lingering dampness. It was around 7 a.m. on May 28 when the Virginians, advancing in single file, came to the rocky precipice overlooking the French camp. Washington was at the head of the column and the first to spot the French who, he later reported, scrambled for their muskets.

The battle lasted only 15 minutes. At least ten French soldiers fell, most of them killed by Washington’s Indian allies. One of those dead Frenchmen was the party’s commander, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville. The mountain glen was a macabre scene of unburied and scalped French corpses, with a Frenchman’s decapitated head stuck upon a pole.

Historians have long identified this skirmish in the woods as the spark that ignited the French and Indian War. But there’s an untold dimension to this story, as I discovered several years ago, digging through colonial papers in the British National Archives.

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair

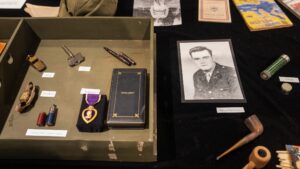

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day

The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day