Photo: Original Law Barracks, from The Citadel Archives

As seen in The Post and Courier, by Thomas Novelly

Hanging above the heads of customers in Kingstree’s aging post office is an 80-year-old mural depicting acres of golden rice fields.

Created in 1939 by Queens, New York-based artist Arnold Friedman, a modernist painter, the image might seem out of place to locals trying to purchase stamps.

But this mural is a survivor, one of 14 works of art that have outlasted decades of remodeling in schools and post offices across South Carolina. It’s a symbol and a relic of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the overwhelming economic and cultural impact its programs still have on the Palmetto State.

“It was highly successful. It was an important stimulus to the South Carolina economy,” said Robert Waller, a retired professor of history from Clemson University and an expert on the New Deal. “Most of those buildings that they built in the ’30s are still in use and still standing today.”

It’s difficult to know the exact number of New Deal projects that were produced as a result of the estimated $42 billion spent nationwide on recovering from the Great Depression. But scholars at the University of California in Berkeley have painstakingly cataloged many buildings, parks and murals created in the United States, including more than 100 in South Carolina.

“The total number of New Deal structures in South Carolina, either originally constructed or still standing, is unknown, and it would take a very large amount of research to get reasonably accurate numbers,” Brent McKee, a scholar with the Living New Deal project, said. “The Living New Deal has documented 130 projects, most still existing.”

The creation of Lakes Marion and Moultrie and the Santee Cooper utility that lit up the state’s countryside was a massive New Deal project. The sprawling 5,000-acre Hunting Island State Park that attracts more than a million visitors a year was created by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The McKissick Museum, located in the heart of the University of South Carolina, was built by a federal government program to serve as the school’s library before it became an establishment recognized for its renowned Southern folk life collection.

Many South Carolina residents frequent several of them a month, for leisure or business. And while not immune to development, remodeling or demolition, very few of the projects identified by Berkeley’s Living New Deal Project have vanished.

Charleston’s New Deal survivors

The financial wave caused by the stock market collapse in October 1929 hit South Carolina hard.

“South Carolina was and is impoverished, poorer than a lot of the other states,” said Kerry Taylor, an associate history professor at The Citadel. “In a way, the Roaring ’20s missed South Carolina.”

In Taylor’s book “Charleston and the Great Depression,” he looks at old City Council meeting minutes and correspondence to get the pulse of Charleston’s woes. South Carolina’s economy had experienced nearly a decade of struggle after the pesky boll weevil insect put a heavy dent in the state’s agriculture and cotton markets. The collapse of Wall Street was seemingly a nail in the coffin for some.

Children in one Charleston family would devour donated potatoes “as others would eat ice cream cones,” Taylor reported. Another family was “kept alive principally on a quart of milk furnished by a dairy and two quarts of skimmed milk furnished from other sources.”

One resident, J.C. Driggers, wrote a line to Roosevelt when he was a presidential candidate where he parodied Psalm 23: “My expenses runneth over, surely my unemployment and poverty will follow me all the days of my life And I will dwell in the house of poverty forever. Amen.”

Soon after Roosevelt’s election, he got to work on passing a multitude of economic reforms and stimulus packages. Of the 130 New Deal projects identified in the state, at least eight were in Charleston.

What is now the Palace Apartments on upper King Street was once the former Charleston County Hall. The WPA spent $250,000 to convert the building into a multi-use facility for basketball, boxing, tennis, indoor track, concerts and dances. Professional wrestling also was held inside the building for years.

The Planter’s Hotel on Church Street likely would have fallen into disrepair if not for a WPA project that remade it as the Dock Street Theatre. Following a $350,000 renovation, the new theater in Charleston’s French Quarter opened and remains one of the city’s most popular and iconic venues.

The College of Charleston’s Student Activities Building and Gymnasium was funded by the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works in 1938 and even featured dorm rooms for out-of-county basketball players. It later was renovated and renamed the Willard A. Silcox Physical Education and Health Center.

Taylor recognized that even his own university, The Citadel, has the New Deal to thank for much of its campus, which was relocated from Marion Square to its current Ashley River location just years before Roosevelt’s election.

Both the barracks and the chapel were a part of a $250,000 construction undertaking. Taylor pointed out that despite the overwhelming conservative political views from The Citadel’s student body, the campus would look completely different without one of the most progressive government projects in American history.

“Half of The Citadel was built with New Deal money,” Taylor said. “The modern campus as we know it was the result of this democratic program. It kept this campus open.”

Nature’s splendor and fading ink

Perhaps the largest impact on South Carolina was the creation of its most noteworthy state parks.

At least 16 parks were created when the Civilian Conservation Corps began work. Waller, in his book “Relief, Recreation, Racism: Civilian Conservation Corps Creates South Carolina State Parks” details the $57 million spent and the work done by 99 CCC camps during the New Deal-era.

Their work includes the notable beach parks at Edisto Island and Myrtle Beach. Table Rock State Park, home to one of the state’s tallest mountains, was also a part of the undertaking.

“They tried to have a state park within 75 miles of every major population area,” Waller said. “It was a success.”

Today, there are 47 state parks in the Palmetto State, and the South Carolina Park Service has generated a record amount of revenue, $34 million for 201819, for the second year in a row.

The creation of Santee Cooper in Moncks Corner was perhaps the most influential project of the New Deal. The utility created and distributed power from hydroelectric dams at the newly created Lakes Marion and Moultrie.

“Santee Cooper really brought South Carolina into the 20th century,” Taylor said. “It’s impact was tremendous and ongoing in terms of developing economic stability.”

While most of South Carolina’s New Deal buildings still stand, a few others have not survived the test of time.

The federal Public Works Administration contributed to the development of Rock Hill’s Arcade-Victoria School, which has since been demolished. The nearby Central School, Northside School and Emmett Scott High School, also New Deal projects, met the same fate.

Some murals have disappeared. Others have found new life. A painting inside the former Summerville post office, an oil-on-canvas mural of residents in Victorian garb boarding a train was painted by Bernadine Custer, managed to outlive the civic building. The building itself is being turned into a creative hub with exhibits, private studio spaces, classrooms and an outdoor stage.

The former post office hopes to be a home for future, civic-minded painters and emerging artists.

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair

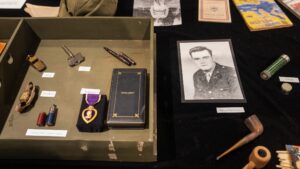

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day

The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day