As seen in The Post and Courier, by Shamira McCray

Photo above: Dr. Scott Curtis turns on his heat-sensor camera along with others participating in the collaborative Heat Watch project around Charleston to record temperatures across the city and determine where heat is most extreme on July 31, 2021, in North Charleston. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staffawhitaker@postandcourier.com

Researchers and volunteers in Charleston joined a national effort in late July to track heat and humidity across the city on one of the hottest days of the year.

On July 31, volunteers traveled across parts of the Charleston area by car and foot to record temperatures, humidity, time and location using special sensors mounted to cars and cellphone cameras.

Data recorded during the citizen science project will be used as part of the national Heat Watch program to learn where action is needed to protect vulnerable populations now and in the future.

Researchers and volunteers in Charleston joined a national effort in late July to track heat and humidity across the city on one of the hottest days of the year.

On July 31, volunteers traveled across parts of the Charleston area by car and foot to record temperatures, humidity, time and location using special sensors mounted to cars and cellphone cameras.

Data recorded during the citizen science project will be used as part of the national Heat Watch program to learn where action is needed to protect vulnerable populations now and in the future.

Researchers and volunteers in Charleston joined a national effort in late July to track heat and humidity across the city on one of the hottest days of the year.

On July 31, volunteers traveled across parts of the Charleston area by car and foot to record temperatures, humidity, time and location using special sensors mounted to cars and cellphone cameras.

Data recorded during the citizen science project will be used as part of the national Heat Watch program to learn where action is needed to protect vulnerable populations now and in the future.

Volunteers picked one of the year’s hottest days to execute their project. At 3 a.m. on July 31, the National Weather Service in Charleston said the temperature at Waterfront Park was 87 degrees. There was a heat index of 106 at that time.

The weather service said temperatures downtown reached 93 degrees that day.

The idea on July 31 was to collect as much air temperature data at the street level as possible, said Scott Curtis, Ph.D., who leads the Lt. Col. James B. Near Jr. Center for Climate Studies at The Citadel. He said scientists do not have a lot of information about that currently.

“Satellites can give us skin temperature or the temperature of the surface, but that’s actually different than the air temperature a lot of times,” Curtis said.

During the heat-mapping project last month, Curtis and Citadel graduate student Bonnie Ertel drove around parts of North Charleston three times — during a morning, afternoon and evening shift — to record air temperature data.

Their route included wooded neighborhoods around Leeds Avenue and Dorchester Road, retail areas near Tanger Outlets and industrial parts of North Charleston surrounding Meeting Street.

Curtis was required to drive no more than 35 mph in order for the censor to record accurate data. So highways were excluded from the route.

“We basically take a lot of backroads, which is good because we want to know, like for neighborhoods, what the temperatures are,” Curtis said. “Where people are living and working, we want to know what the temperature is like.”

Curtis said it will be interesting to see how the heat and temperatures vary in different parts of the city.

Ertel commended Heat Watch partners for making the project local and more applicable to the people who live in the area.

“I think it’s neat to be part of climate research kind of where I live,” Ertel said.

The data collected last month will help to shape city policy from zoning codes to what kinds of trees are planted, according to Mark Wilbert, chief resilience officer for Charleston.

In April, Wilbert said Charleston’s recent vulnerability assessment for hazards like earthquakes, hurricanes and sea-level rise indicate “at a very high level” that extreme heat and its effects on the city’s occupants pose a threat.

The data from the project on July 31 will be analyzed by collaborating organization CAPA Strategies. Curtis said the findings of the project should be ready around the end of September.

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair

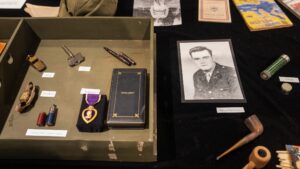

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day

The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day