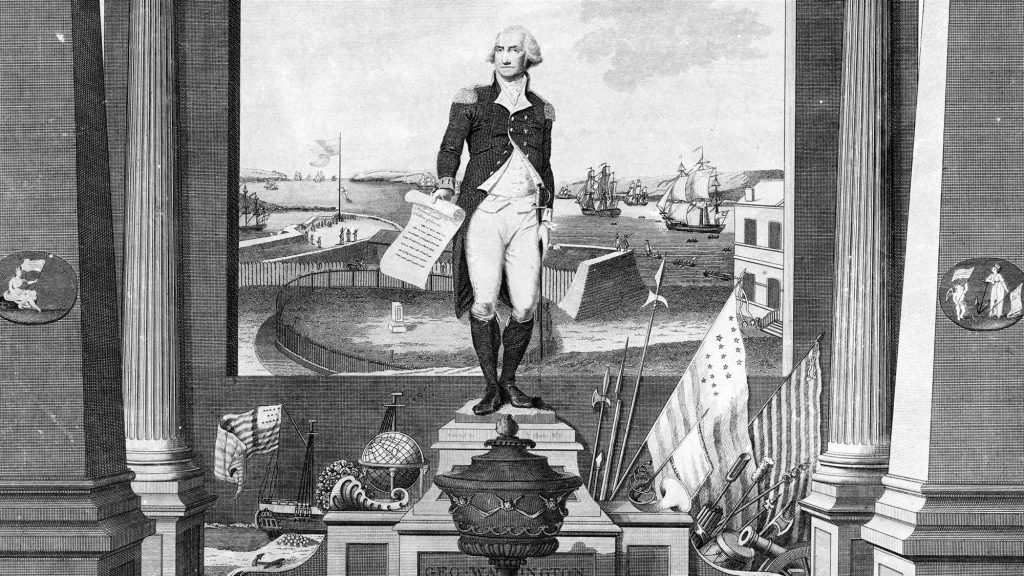

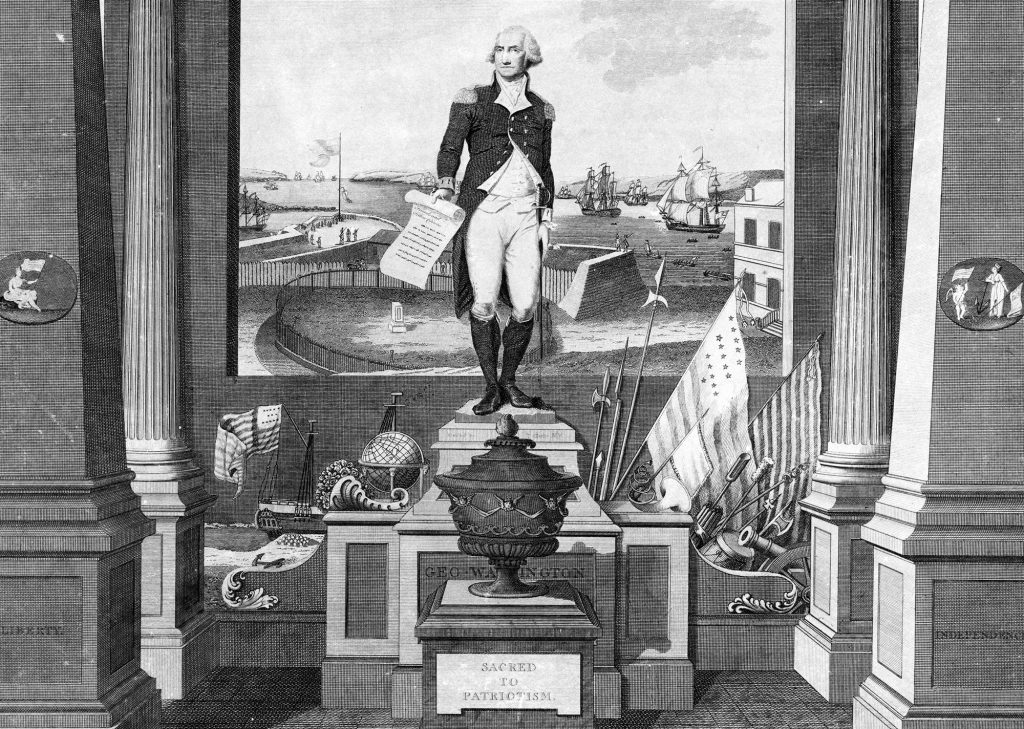

Photo: An engraved portrait of George Washington holding his Farewell Address.

Note: Jacob Hagstrom, Ph.D., is a new professor in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences. He teaches Leadership in Military History and History of the U.S. Military as a member of The Citadel’s History Department.

As seen on NBC Think

By Jacob Hagstrom, Ph.D.

Tuesday night’s verbal brawl between the presidential candidates broke nearly every rule of debate decorum short of a descent into physical violence. The rules dictating equal time for both sides and restraint from interruptions might seem trivial, but their contravention in Cleveland is significant for more than its denying the American people the opportunity to hear clear and contrasting views about the country’s most pressing issues from the two people poised to run it.

It was also a breach of the more fundamental values supporting American democracy: deference to established norms, respect for different points of view and reasoned debate. Because what makes America work isn’t just the brilliance of the U.S. Constitution in laying out a balance of powers and restraining any one individual from becoming a despot. It’s also because those individuals choose to subordinate themselves to those laws and accept them peacefully without resorting to force. Such action could quickly override the words written on paper.

Which is why it was even more troubling to hear President Donald Trump refuse to forthrightly answer moderator Chris Wallace’s question about whether he would urge his followers not to engage in civil unrest until the end of a potentially lengthy ballot-counting process in November.

While it’s easy to dismiss the president’s response when asked these kinds of questions as mere political jockeying not to be taken seriously — and indeed, that is likely the fact of the matter — it is still important that we remind ourselves of the underlying fragility of our system and what’s at stake.

It was very much a question whether the world’s first experiment with the republican process would succeed back in the late 1700s. It’s only now, centuries later, that we take voluntary departure from high office after the completion of the appointed term as a matter of course. And we can take it for granted because the Americans before us chose to follow those principles.

In fact, the concept of a peaceful transition of power was so revolutionary that even many of the framers of the Constitution themselves hesitated to count on it. They were wary of the risks of concentrating federal power in a single executive and feared that the tyranny of the federal government would be worse than that of Britain. Samuel Adams, among many leaders of the patriots of 1776, believed that the new government would be filled with an aristocratic ruling class and that the very act of centralizing the government would breed striving politicians who would oppress their ordinary constituents.

The reluctance of many framers to sign the Constitution was eased only by their virtually unanimous respect for the leadership of George Washington. Some at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 agreed to its strengthening of executive power only after being reassured that Washington would come out of retirement to accept the presidency.

Like Trump, our first executive was fabulously wealthy, and, alongside Benjamin Franklin, he was one of the biggest celebrities in the Atlantic world. But Washington’s stature was due to his republican values, based on the ancient Roman archetype of Cincinnatus. Washington and his supporters believed that the greatest honor was due a successful general who gave up public power to enjoy private life.

That creating the office of the presidency in the young United States was largely dependent upon having the right person to fill the role indicates how shaky the concept was at the time and how essential the model of Washington was.

Thankfully, Washington was aware of his role in history and establishing a republican tradition. His widely circulated Farewell Address made clear the importance of his stepping down from presidential power in 1797 rather than pursuing a third term in office. In part, Washington sought refuge from the national stage after a lifetime of diplomatic and military service. In a private letter to Alexander Hamilton, Washington revealed that he also sought to avoid abuse “in the public prints by a set of infamous scribblers.”

But though Washington’s retreat from the public spotlight went off without a hitch, it wasn’t enough to secure the principle of the peaceful transfer of power. The first genuine fears of violence during an American transition came soon enough, when Washington’s successor, John Adams, ran for re-election in 1800. In the shadow of the French Revolution, there were fears across the Atlantic that republics could not long survive.

Part of the novelty of the election was that a small but aggressively partisan press had developed by 1800. The partisan “scribblers” whom Washington bemoaned trafficked in fears that the election of the leader of either budding faction, Jefferson or Adams, would result in mobs spreading “villainy and bloodshed.” Of course, none materialized.

But political violence remained an ever-present threat in the early republic, usually taking the form of former military officers going rogue, like Aaron Burr, who tied Jefferson for the most electoral votes in 1800 and lost the vote in the House of Representatives. Burr went on a campaign to stir dissent, with critics accusing him of treason — specifically, plotting to form a breakaway republic in the West.

But Washington’s example of disinterested leadership proved stronger than such challenges, even when the most serious threat to the transfer-of-power tradition emerged in the contested election of 1824. That year, military hero Andrew Jackson, famous both for duels and for leading an unauthorized war against the Seminoles, won a plurality of the popular vote and more electoral votes than his two main rivals, the aristocratic John Quincy Adams and Sen. Henry Clay.

But none had a majority in the Electoral College, so the House of Representatives decided the election. The legislature decided against Jackson, even though by all democratic logic he was the choice of the people, in what Jackson denounced as a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and Clay.

Though Jackson was, in fact, accustomed to personal and military violence, he abstained from “the Society of both intriguers and Caucus mongers,” writing, “If ever I fill that office, it must be the free choice of the people — I can then say I am the President of the Nation — and my acts will comport with that character.” Jackson simply waited as states began to allow property-less white men to vote, which he correctly calculated would score him a landslide victory in 1828.

Instead of challenging the integrity of the democratic system, Jackson merely challenged that of contemporary political parties. Trump, too, likely represents only the breakdown of the current two-party system rather than a breakdown in society and geopolitics at large.

Jackson’s populism led to the growth of the anti-Jackson Whig Party in the 1840s from the wreckage of the old Federalist Party of Hamilton and the elder Adams, as well as anti-Jackson Democrats in the mold of the more principled and erudite Jefferson. The new Whigs remained a check on Jacksonian Democrats until the sectional crisis of the Civil War era reorganized the party system once again.

Many aspects of political culture in the era of Jackson — populism, racialized thinking and the favoritism of a nepotistic governing system — have re-emerged as pressing problems. But these problems didn’t lead Jackson to try to hold power unlawfully, even as many feared what the galvanizing of disaffected poor white men would mean for the republic.

Today, Americans must hope that Trump’s threats to remain in power against the wishes of the people are as empty as his threats to “build a wall” or “lock her up” and that, like his hero Jackson, he, too, follows in Washington’s footsteps.

Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine

Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine The Citadel recognized as Top 10 Military Friendly employer for 2026

The Citadel recognized as Top 10 Military Friendly employer for 2026 Citadel dean named to South Carolina Humanities board of directors

Citadel dean named to South Carolina Humanities board of directors