Photo above courtesy of the United States Marine Corps

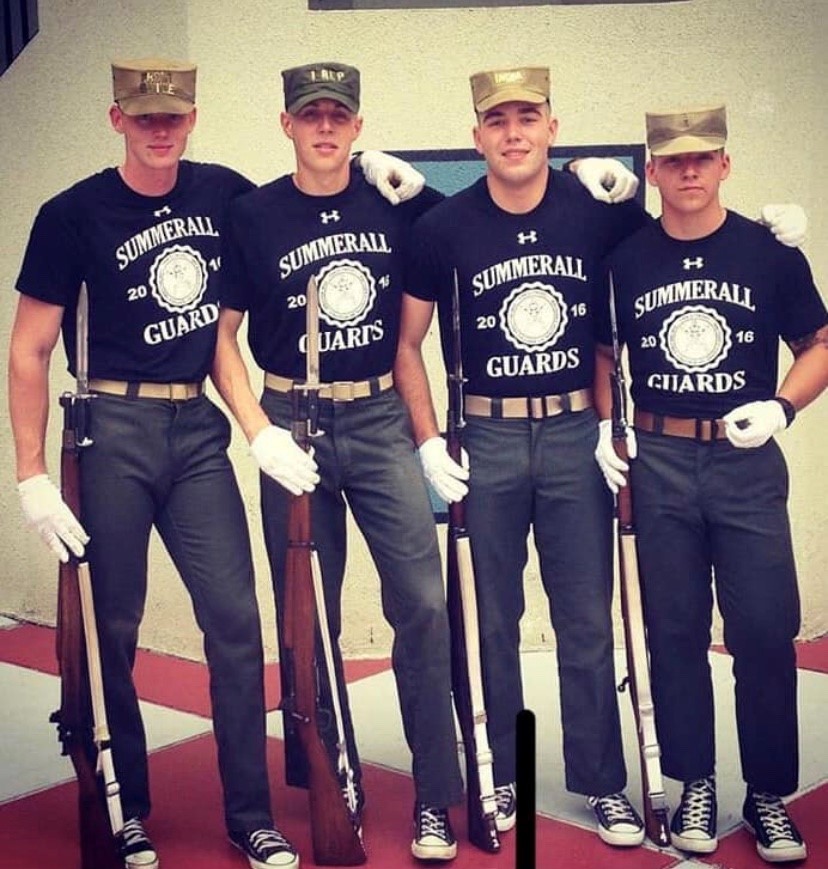

Note: Matthew Kraft graduated from The Citadel in 2016. Upon graduating, Kraft was awarded the Lt. Dan Malcomb Sword in recognition of Kraft’s leadership and dedication while a member of The Citadel Naval ROTC unit. Additionally, Kraft was an exemplary student, earning Gold Stars, President’s List and Dean’s List accolades repeatedly while attending The Citadel. He graduated with a degree in Political Science. Additionally, Kraft was a member of the elite senior cadet drill team, The Summerall Guards, who are selected after months of physical training and drilling competitions.

View a photo gallery provided by one of Kraft’s classmates and fellow Summerall Guards, 1st Lt. Tyler Treadaway, currently serving as an Apache helicopter pilot for the United States Army in Hawaii.

As seen in the Orange County Register, by Erika I. Ritchie

Every night, Greg Kraft turns on an electric candle that sits in the window of his family’s Connecticut home.

“I turn it on and I say, ‘God Bless Matt,’ ” Kraft said Friday, Feb. 21, his voice choked with emotion. “In the morning I turn it off and say ‘God Bless Matt.’

The candle, in the upstairs middle dormer of his Williamsburg Cape Cod-style home, is lighted so his son, Capt. Matthew Kraft, can find his way back.

Matthew Kraft, a platoon leader with the 1st Battalion/7th Marines at Twentynine Palms, part of the 1st Marine Division based at Camp Pendleton, disappeared after taking leave from the Marine Corps for a two-week backcountry ski trip along the High Sierra Route starting Feb. 24, 2019.

He had planned the rugged trek for his pre-deployment leave, before his unit was to depart for Afghanistan.

The Sierra High Route parallels the John Muir Trail, with elevations ranging from 9,000 to 11,500 feet. The nearly 200-mile hike that began in the Inyo Forest near Lone Pine was supposed to be completed over 10 days, and Kraft had notified family and the Marine Corps that he expected to arrive at Bridgeport March 4 or 5.

Matthew Kraft spoke with his father for the last time two days before setting out on his hike and Greg Kraft told him to be safe.

Kraft has kept the candlelight vigil going since March 16, the day after the Marine Corps officially pronounced his 24-year-old infantryman son dead.

Massive multi-agency search

For more than a week, 13 agencies — including the Marine Corps from the Mountain Warfare Training Center in Bridgeport — searched for Matthew Kraft.

His rental vehicle was found near Grays Meadows campground above Independence on March 8. On March 9, a ground search was halted after rescuers came across massive avalanche debris fields and officials with the Inyo County Sheriff’s Department declared conditions too risky for search crews to continue.

They shifted to an aerial search, focusing on the Sequoia and Kings National Park which extends along approximately 70 miles of the Sierra High Route. When thermal imaging from low-flying aircraft picked up a heat spot, Greg Kraft and his family were hopeful that Matthew Kraft might be found. But upon closer inspection, search crews found it was a hibernating bear.

“That’s when I came to grips with it,” said Greg Kraft. “It’s also the day (March 15) the Marine Corps calls the date of death.”

An official statement, released by the Marine Corps on April 11, said Matthew Kraft died after being “overcome by severe winter storms.”

Kraft was posthumously promoted from 1st Lt. to the rank of Captain.

n August, with most of the snow melted and the granite rocks exposed along the sub-alpine terrain, Greg Kraft, his wife, Roxanne and daughter, Ashley, saw a chance to search once more and possibly end the pain of waiting for a definitive answer.

But despite hundreds of fliers being handed out to hikers in the area and search teams combing for evidence, there was still no sign of Matthew Kraft.

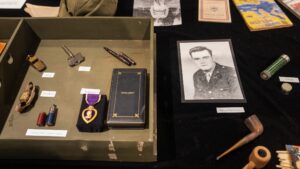

In September, the Kraft family held a memorial service for Matthew Kraft near their home, at the First Congregational Church of Washington. More than 250 people came to pay their respects in the small New England town of 3,300.

The event was held to acknowledge the loss and to allow friends and family to say goodbye.

“The interim period was tough as people didn’t know how to discuss … ‘Are they still looking?’ ‘What’s the plan?’ ‘What are the next steps?’ ‘We’re praying for his safe return,’ ” said Greg Kraft.

“It seemed it was time to allow everyone to grieve.”

In a 56-page memorial book compiled by the Kraft family, relatives and friends described Matthew Kraft as a sweet and honest young boy, a responsible and driven teen at Kent School — a private college preparatory school — and an incredibly fit and conscientious officer-in-the-making at the Citadel military college in South Carolina.

His Marine colleagues praised him for being an exceptional officer, unlike any they had ever met.

“Many Marines say they love the Marine Corps,” wrote 1st Lt. Isaiah Jurado, a platoon leader in the same company with Kraft. “They get tattoos of the (eagle, globe and anchor) on their chests and put stickers on their cars to let everyone know. But a special kind of Marine needs no words, symbols or proclamations to describe their love for the Corps. Their love is found in late nights at the office, their stoicism in harsh conditions, genuine concern for subordinates and an obstinate adherence to what is right, regardless of the situation. These Marines live on through their influence and deeds, setting the example for the rest to come. Matt was one of these Marines.”

A meticulous plan

Matthew Kraft received approval from the Marine Corps before setting off on his backcountry trek. Typical leave plans include a list of locations where the Marine intends to stay while away from base and information on how the Marine might be reached if needed.

“He had very meticulously planned the trip, he loved the outdoors and skiing,” said Jurado, who had offered to pick Kraft up at his Bridgeport destination.

Jurado, 28, left Los Angeles March 3, where he was visiting family, and drove along U.S. Route 395 which runs along the Eastern Sierra. As he glanced at the mountain range, he recalled, he had full confidence in his friend’s ability to navigate the remote terrain and austere weather conditions.

Jurado, who had met Matthew Kraft a year earlier, was impressed with Kraft’s innate ability as a platoon officer and Marine.

“He was so focused,” Jurado said. “He was a standout guy in the truest sense. He knew what he was doing. He was so confident in himself.”

That confidence resonated with Jurado, so when he didn’t hear from his friend on the day he was expected to arrive in Bridgeport, he wasn’t concerned. Matthew Kraft had taken extra rations and built in several days in case of changes he might encounter.

But on March 5, when Jurado still hadn’t heard from him, he decided to head toward the trailhead near Bridgeport where the two had planned to meet. It was a calm snowy day, he recalled. A storm had just passed and he could feel the makings of another storm in the air.

He wanted to cover as much ground as he could before the next storm arrived.

“I drove to the trailhead and stayed there for most of the day,” he said. It was a call from Greg Kraft, Jurado said, that “raised the flag.”

“Maybe he bailed out along the route, maybe he hunkered down in the storms,” Jurado said. “I started thinking through scenarios and I wanted to stay positive.”

Remembering a friend

Jimmy Lozano, a 71-year-old Vietnam veteran who shared Matthew Kraft’s love of mountaineering and was a neighbor of the Marine’s in Twentynine Palms, was among those who shared fond memories with the Kraft family.

“Although there is a big gap in age difference, we connected in a tight friendship,” the Long Beach native wrote to the Krafts. “Matt was, and still is in my book, a friend beyond any possible definition Webster’s dictionary can come up with. I’m completely heartbroken to the fact that Matt’s disappearance is becoming reality.”

Lozano and Kraft spent a lot of time talking about the mountains, he said.

Kraft was an avid mountaineer and told his friend of a 14-day hike he made of the Cohos Trail that goes from New Hampshire to Canada. He hiked 40 peaks in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and had plans to hike the Appalachian Trail. Kraft had twice gone through mountaineering training with the Marine Corps at Bridgeport, preparing for high altitudes and austere conditions.

Lozano told Kraft about mountains surrounding the base and talked about training opportunities for what he called Kraft’s “bucket list” goal of hiking the Sierra High Route.

Each weekend, Lozano said, Kraft took trips into local mountains. He also had hiked the Sierra High Route in the summer of 2018 to get an idea of what the trail would be like.

“He showed me pictures of catching trophy-sized brook trout and setting up his tent in the backcountry,” Lozano said. “He said the area was beautiful and he had it in his mind to hike there ever since he came to California.”

When Lozano found out Kraft was planning to do the trek alone in the winter of 2019, he cautioned him.

“I told him I wouldn’t do it alone,” Lozano said. “The severity of the Sierras is a lot different than the East Coast with avalanches. He told me, ‘I’ve got it pre-planned and I’m going for it.”

A final resting place

Now, the Kraft family has purchased a gravesite and ordered a headstone. They hope that the site may one day be the final resting spot for Matthew Kraft and where his ancestors will remember him. On the headstone, the family has engraved: Aug. 23, 1994 – 2019.

Though Greg Kraft said he will never have closure until his son is found, he hopes that one day he at least will determine exactly when he died.

“They (the search team) spent a lot of time at the pass,” he said. “He would have hit that on day one or two. I think he got through the pass. I think he got through bad weather. He was an animal. He was strong as a moose. He traveled 30 miles a day in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. It would put a date on when he really passed.

“Without that, it’s going to be three weeks of mourning every year,” he added. “It’s 365 days of mourning now.”

Photos in gallery below courtesy of 1st Lt. Stephen Tyler Treadaway, United States Army, Citadel Class of 2016.

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day

The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day