As seen in South Carolina Radio Network, by Renee Sexton

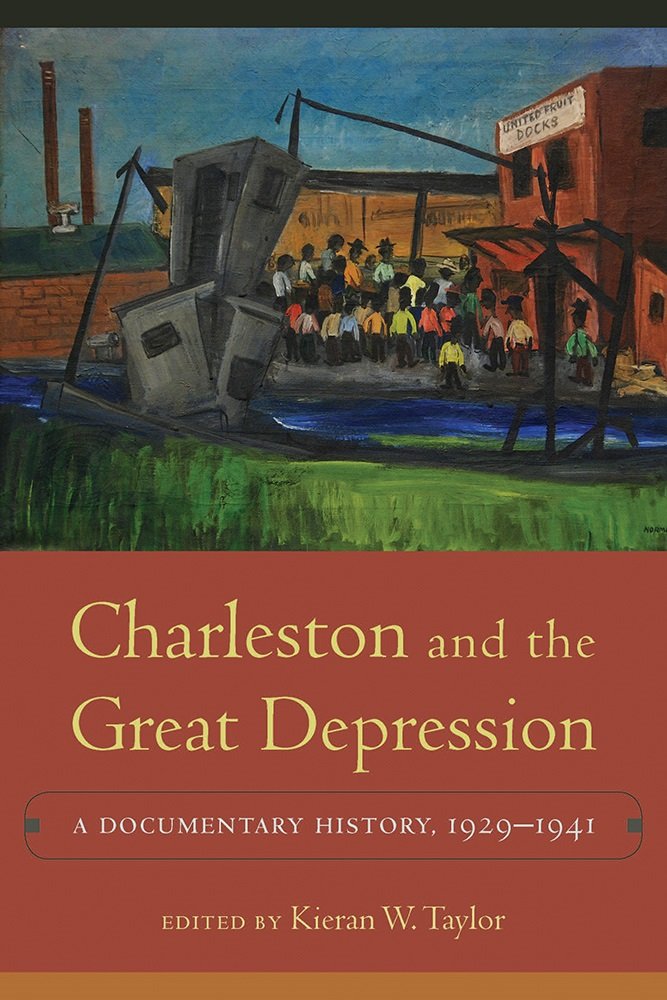

A Citadel history professor has turned a class project into a new book of documents about the Great Depression in Charleston.

Dr. Kieran “Kerry” Taylor just released Charleston and the Great Depression A Documentary History 1929-1941 compiled from work he did with his Historical Methods Class for sophomore history majors. The book includes a series of primary documents that reveal how people of the Lowcountry survived the Great Depression.

At the time Franklin Delano Roosevelt was first elected, roughly one out of every four Americans was out of work. Taylor said 20 percent of Charleston’s workforce was unemployed. Roosevelt’s remarks at the Citadel in October 1935 are included in the book.

“He developed strong personal relationships with some key South Carolina politicians,” Taylor said. “The South was a key component of the New Deal Coalition or the Roosevelt Coalition. It was important for Roosevelt to keep the Democratic Party and to keep South Carolina happy. So South Carolina received very consistent and strong support from the federal government during the New Deal era.”

Prior to the passage of the Voting Rights Act, “this was an all-white Democratic party in South Carolina and even then, if you look at the numbers of people who were voting, it’s just a fraction of the number of adult South Carolinians,” Taylor said. “The Republican Party was really a non-entity in Southern politics during the 1930s. It’s a one-party state.”

“The South and South Carolina were strong supporters of Roosevelt and the New Deal and he responded in kind,” he said.

Taylor said Charleston was so poor when Burnet Maybank was inaugurated as Mayor in 1931, there was no cash to pay employees. Some were paid in scrip which was accepted at Charleston-area businesses.

“The city was poor,” he said. “South Carolina’s economy suffered tremendously (after World War I).”

“Farmers were devastated both by the boll weevil but also collapsing prices for commodities, especially cotton, ” Taylor said. “And because much of Charleston’s economy depended on the import and export of cotton, the city found itself strapped for many, many years.”

Taylor said Maybank’s commitment to the New Deal helped Charleston recover. A common theme of the book is the impact that common people had on politics. It includes several letters South Carolinians wrote to President Roosevelt asking for his consideration on certain issues, such as social security to condemning mob rule and lynching. Some of the letter writers were black men who were denied the right to vote.

“Even with a system that is as undemocratic as South Carolina politics were in the 1930s, just regular working folks had ways of acting politically,” he said. “This larger theme of the ways in which grassroots pressure could be directed and could transfer from ordinary politicians and community leaders to do some pretty extraordinary things. And it’s driven by a deep faith that the American people had in the power of government to do good things . . . they were committed to holding their elected officials accountable one way or another.”

Taylor said that idea resonates in the present.

“I think the 1930s, in that sense, represent a real antidote to the kind of cynicism that many of my students and many Americans, I think, approach government today,” he said.

Taylor said the New Deal helped Charleston survive the Great Depression.

“Our institutions were stabilized. The New Deal saved the College of Charleston. It saved the Citadel. it saved the city government from complete collapse,” he said.

Taylor’s book is available through the University of South Carolina Press.

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine

Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine Citadel professor to serve as next Inspector General for the U.S. Department of Defense

Citadel professor to serve as next Inspector General for the U.S. Department of Defense