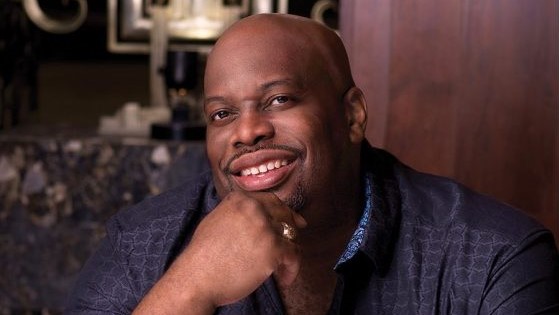

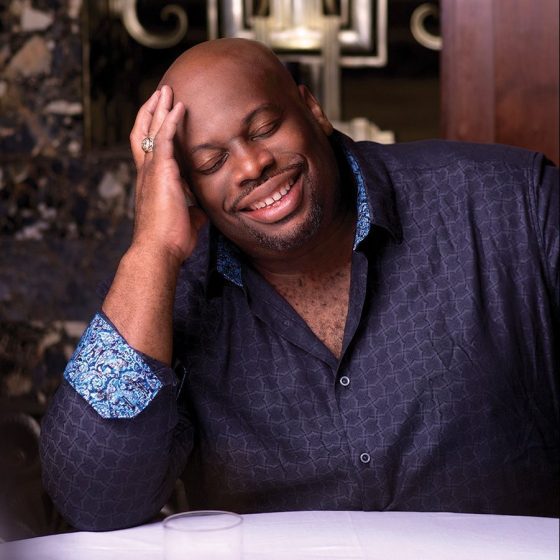

Photo: Morris Robinson, ’91 (Courtesy: Tina Gutierrez)

As seen in Movers and Makers Cincinatti, by Julie Kemble Borths

Growing up into a muscular, African-American man in the American South, Morris Robinson knew about being pigeonholed into a role. “I used that to my advantage,” he recalled. “Where I come from, playing football was the way you got respect.”

Although he sang in choirs, attended a performing arts high school and played drums, he made his way onto the field and made a name for himself.

At The Citadel, he was an All-American, but he was too small for the pros and began a corporate career. Encouraged by friends and family, he finally committed to serious vocal training and his opera career began when he was cast in “Aida” in 1999.

He quickly learned from other African-American singers to avoid one role for a while if he didn’t want to be pigeonholed.

“Porgy,” he said, referring to the title role of the landmark “Porgy and Bess” by George and Ira Gershwin. The composer had stipulated the 1935 piece must always have a black cast and Robinson knew if he sang it too soon, it might be the only role he was ever offered. “I may have come to opera late, but I met people right away who became my mentors and let me know to stay away from that role,” he said.

But this month at the Cincinnati Opera, he will indeed step into the role of the disabled beggar who loves the beautiful Bess. Caught between her violent lover Crown and her drug dealer, Sportin’ Life, Bess is scorned by her community on Catfish Row and only experiences true love from the innocent, honest Porgy.

It’s not that he dislikes the role. Robinson relishes the opportunity to delve into a part that goes well beyond the stereotype. “Porgy has been a challenge because certain directors want to see Porgy in a different way. You know, ‘poor little Porgy.’ That’s not me. Porgy kills Crown with his bare hands. This isn’t the Porgy people think of very often. But they should. … There is so much more to Porgy. There’s that inner rage – he’s been crippled all his life and is jealous of the guy whose legs do work. This is his one chance for love.”

Robinson didn’t play Porgy until 2017, after nearly 18 years in roles across the classic European opera repertoire. He chose the moment carefully: It was at Teatro alla Scala in Milan, the premiere Italian opera house.

“There, I knew it would be a challenge,” he said. Before that, he said, there was a chance he would limit his training and exposure as well as his potential to support himself if his career was bounded by roles like Porgy and songs like “Ol’ Man River” from “Showboat.”

“As a young artist, you go to these dinner parties after you have sung some of the most complex and demanding works of the Italian and German repertoire, and people say, ‘I bet you can sing “Ol’ Man River,” ’ ” Robinson said.

“You want to say, ‘I just got done singing Verdi. Did you hear me? I just sang Sarastro in German (from Mozart’s “The Magic Flute”). Did you hear that?”

Respecting the full breadth of talent in singers, and not the role their physical appearance might first suggest, is a serious responsibility for opera companies, said Evans Mirageas, artistic director for Cincinnati Opera.

The company’s commitment to diversity is evidenced by the casting of “Porgy and Bess.” The principal roles were filled by singers who have performed core opera repertoire with Cincinnati Opera. Soprano Janai Brugger, for example, just completed Mozart’s “Marriage of Figaro” here in the role of Susanna. And Robinson is familiar to local audiences, including a performance this spring in the May Festival’s Mahler and Mussorgsky program.

He first performed with Cincinnati Opera as the Grand Inquisitor in “Don Carlo” and returned several times in classic roles, then accepted a three-year appointment in late 2017 as the company’s artistic adviser. In that capacity, he has traveled throughout the community, promoting opera and broadening its audience.

One way he does this is with young people, such as the high school students in David Dendler’s class at Princeton High School. Dendler said Robinson’s imposing presence was a contrast to the gentle coaching he offered the students, focusing on musical phrasing and breath control.

“One of the kids literally doubled his sound working with Morris,” Dendler said. “I saw (the student) later that day in the hall, and he literally would not stop smiling. It was such an ‘aha’ moment for him. He will not forget that for a lifetime.”

Robinson said his own “aha” moments are unforgettable. There was the first time he auditioned for a chorus and got a role instead; he didn’t understand what had happened until he saw everyone else’s reaction. And there was the time, when beginning his career, he auditioned at the Metropolitan Opera for a young artist program and was offered a position. He called his father, a Baptist preacher, and tried to explain the moment to him. “It was like you giving a sermon and Jesus was in the pew.”

As a bass, he often played what Mirageas calls the “dad or the bad,” classic roles for that voice type.

“I’m very aware of what I look like. I’m this big, bald, intimidating-looking guy. I think it’s helped my operatic career because of the type of characters I can play. I just walk on and they – the audience – can say ‘I know that guy,’ ” Robinson said.

“Most of the characters I play walk out on the stage and demand change. I am a high priest or I am the devil,” Robinson said. His characters often have a singular motivation of: “You will listen to what I say while I make this proclamation.”

But when he first opened the score for “Porgy and Bess,” he said, he found he needed to expand his emotional capabilities onstage.

But he was confident he could do the role. “I went through every note. I was psyched. I kept thinking, ‘Where’s the hard part? Where’s the part that I can’t sing?’ By the time I showed up for the first rehearsal at La Scala, I didn’t even take the score with me. I was all ready.”

In Cincinnati, with a fully staged production unlike some of the others, he again is preparing to immerse himself physically and mentally in Porgy. “This is a real deal. Really top to bottom.”

Robinson, Mirageas said, brings a nobleness to Porgy. “He’s really the only one who believes in love,” he said. “He’s the only one who’s not cynical.”

Mirageas said, “It’s an opera that teaches us that strength comes in many forms.”

The opportunity is not lost on Robinson.

“Porgy and Bess” will bring audiences their own “aha” moments, along with other operas as casts become more diverse and singers can be more diverse in their repertoire than their skin color might suggest, Robinson said.

“I think we are getting better at having conversations about it because there are courageous people who are speaking out,” Robinson said. “It’s causing the industry to take notice. After all, if we want everyone’s business, our view can’t be as narrow.”

The Citadel’s presidential search committee announces four finalists

The Citadel’s presidential search committee announces four finalists Prestigious Cincinnati and MacArthur awards presented to Citadel cadets

Prestigious Cincinnati and MacArthur awards presented to Citadel cadets Looking ahead to the major events of 2026-27

Looking ahead to the major events of 2026-27