As seen in The Post and Courier, by Brian Hicks

U.S. District Judge Patrick Michael Duffy has spent his life walking among giants, brushing shoulders with legends.

And he held his own.

As a young attorney in Charleston, Duffy never aspired to a federal judgeship. He was happy litigating cases in the courtroom — fighting for his clients, defending the accused.

“That’s all I ever wanted to do; I never even thought about the bench,” Duffy recalls. “Those positions were for people like Judge Blatt and Judge Perry.”

But in 1995, opportunity called. U.S. District Judge Matthew Perry was retiring, and Sen. Fritz Hollings wanted Duffy to take his place.

Duffy was overwhelmed. Perry was a legend, South Carolina’s greatest civil rights attorney, the man behind Harvey Gantt’s integration of Clemson, the state’s first black federal judge. Some suggested another African American should take his place, but Perry shut that down fast.

“He doesn’t have to look like me to be a great judge.”

Judge Duffy proved him right. In 2003, he ordered Charleston County to elect its council by single-member districts, ensuring black voters a more level playing field in local government.

He was following in the tradition of excellent Charleston federal judges going back to Waties Waring, whose name adorns the federal courthouse where he’s worked for 23 years.

Today, Judge Duffy retires a giant.

A thoughtful man

Judge Duffy is a kind man, a gentle soul with a sharp wit, empathy to spare and a sense of history.

All ideal traits in a federal judge.

In some circles, he’s perhaps better known as a community activist. He was instrumental in building the Irish Memorial Park at the end of Charlotte Street and the statue of two Citadel classmates killed in Vietnam that stands in the south end zone of Johnson Hagood Stadium.

When his alma mater was struggling with co-ed cadets, he brought in Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor to address the corps.

Judge Duffy always knew the the right thing to do.

His colleagues marvel at his work ethic. When he receives a pre-sentencing report on a defendant, Judge Duffy starts in the back. The first pages are filled with the defendant’s criminal record; the back details his family history.

“It tells you about their upbringing and other factors,” the judge says. “Sometimes they help you see what might have led them to do something. You can put it in better perspective. That may not be an excuse, but it’s a good explanation.”

Judge Duffy says Judge Sol Blatt Jr. — a man he could not help but address as judge, even after they became colleagues — set the standard for modern U.S. District Court. But he has undoubtedly continued it.

He says an independent judiciary is essential for our government, and laments that it is under attack. People need to understand, it’s all there in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The founders knew the executive and legislative branches would clash; it was up to the judicial branch to referee.

“The Founding Fathers set it up wonderfully,” he says.

And Duffy has been the model of that system.

His place in history

The judge’s chambers are quiet now. The law clerks left in August, and most of the offices are empty. But the photos on the walls still talk, and they say that Judge Duffy was witness to the most storied moments of his generation.

He was at The Citadel when Pat Conroy first ran afoul of a commandant of cadets called The Boo. His classmates and running buddies at USC’s School of Law are a who’s who of South Carolina history.

His former roommate, Joe Riley, went on to become mayor of Charleston; Bob Sheheen was the future state House speaker. I.S. Leevy Johnson, the law school’s first African-American graduate, became one of the first black state House members since Reconstruction and first black president of the South Carolina Bar Association.

Jean Toal and Costa Pleicones both later became chief justice of the state Supreme Court.

“Jean was the only one we were sure would make it big,” Duffy says with a laugh.

But Judge Duffy fits in perfectly with that distinguished crowd. When he ordered the county to institute single-member districts, Riley sent him a note that said, “Judge Waring would be proud.”

As should everyone.

Judge Duffy and his wife, Kathy, plan to travel, spend time with their grandchildren. But today, public defenders, probation officers and his fellow jurists will celebrate his 50 years in the service of justice — 27 as an attorney, 23 as a judge.

Surrounded by history all his life, he made his own.

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair

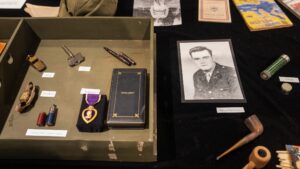

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day

The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day Academy of Engineers inducts four new honorees during The Citadel’s School of Engineering event

Academy of Engineers inducts four new honorees during The Citadel’s School of Engineering event