As seen in The Post and Courier, by Shamira McCray

Photo above from Post and Courier/Andrew J. Whitaker : The sun cut’s through the haze as Lucy Beckham High players run blocking drills during practice in late summer 2020.

Note: article includes input from The Citadel’s Near Center for Climate Studies

Although some of the most apparent impacts of the Earth’s changing climate are rising waters, extreme temperatures and other major weather events, this global issue has turned out to be a public health crisis for vulnerable populations, too.

And children are among the most endangered.

Increasing temperatures, air pollution and extreme precipitation has led to heat-related deaths, asthma and even waterborne illness in children. And health experts say sicknesses like these are likely to get worse over the next decade.

Increasing temperatures

Climate change is causing temperatures to rise. Maximum temperatures for all seasons in Charleston have steadily increased over the past 100 years.

Being exposed to high temperatures can cause heat-related illnesses like heat stroke, exhaustion and rashes, medical experts say.

Dr. Hayley Guilkey, a pediatrician and founder of the S.C. Health Professionals for Climate Action organization, said elderly people have the greatest risk for heat illness, but children — particularly student athletes and infants — are also at an elevated risk.

According to Guilkey, heat illness is the leading cause that puts high schools athletes at risk of death. She said more than 9,000 heat illnesses are reported each year among this group, and they account for over a third of the nation’s emergency room visits.

Some of these illnesses, such as dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, are peaking right now.

“We see they occur most frequently in August when preseason sports are beginning, kids haven’t necessarily been training while over the summer, and it’s extremely hot,” Guilkey said in a Medical University of South Carolina children’s health and climate change webinar earlier this month.

In 2018, the S.C. High School League and S.C. Independent Schools Association passed regulations that required teams to monitor the heat during outdoor activities with a wet bulb globe thermometer. The device takes into account air temperature, humidity and wind to produce a reading that determines how much and how long teams can practice.

If the thermometer reads 92.1 or higher, all outdoor activities would have to be canceled, according to a previous Post and Courier report.

A child’s immature thermoregulation, high metabolic rate and dependence on caregivers are a few factors that put them more at risk for heat illness.

Right now, infants suffer the second-highest rate of heat-related deaths, after the elderly, and some studies project they will experience the greatest increase in mortality rates due to rising global temperatures, Guilkey said.

Just last year, she saw firsthand the effects heat can have on a baby. During the webinar, she told a story of a child who was riding around in a car with no air conditioning in the middle of summer. The child developed heat illness and dehydration and had to be hospitalized.

“Luckily that baby made a full recovery, but it’s still a scary thing and something that we worry about,” Guilkey said.

Records from the S.C. State Climatology Office show Charleston International Airport saw an average of 57 days per year with temperatures greater than 90 degrees from 1938 to 2020. Through Aug. 18, there have been 32 90-degree weather days just since the start of May, with eight recorded this month alone, at the airport.

Researchers and volunteers set out last month to track heat and humidity across the city on one of the hottest days of the year, July 31. It won’t be until the fall before an analysis of the heat-mapping project is released identifying the most vulnerable parts of Charleston, but scientists and medical experts already know the rising temperatures are taking a toll on humans.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said staying cool, hydrated and informed are some of the best tips to beat heat-related illness.

Air pollution

Dr. Scott Curtis, director of the Lt. Col. James B. Near Jr. Center for Climate Studies at The Citadel, said air quality goes down as temperatures go up. On very hot days, especially days that are stagnant, there isn’t a lot of airflow.

Ozone is a gas composed of oxygen. But at the ground level it can be a harmful air pollutant because of its effects on people and the environment, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Ozone is one of the main ingredients in smog, and exhaust from cars aid in its creation. It degrades the planet’s protective layer of upper atmosphere from some solar radiation.

On the West Coast in places such as California, smoke from wildfires are a major source of air pollution.

Guilkey said poor air quality impacts lung development in children and worsens asthma and other breathing issues.

“With higher minute ventilation — which is how fast they breathe and how much air they breathe in — this exposes them (children) to higher doses of air pollutants such as ozone,” Guilkey said.

A study published by the National Library of Medicine showed an effort to reduce Atlanta traffic during the 1996 summer Olympics could have impacted ozone levels. During the Olympics that year, ozone concentrations were about 30 percent lower than four weeks before.

Guilkey said, more importantly, it led to more than a 40 percent decrease in emergency room visits for children with asthma.

Extreme precipitation

Water-related infections are made worse by climate change, mostly due to an increase in extreme precipitation events.

Data from the State Climatology Office shows there are only about four days per year when precipitation of at least 2 inches is recorded at the airport in North Charleston. These are considered heavy precipitation events. So far this year, there were only two days when the airport’s gauge recorded at least 2 inches of rain, according to the National Weather Service. But in July, rainfall totals exceeded the average 6.60 inches at the airport.

In Charleston especially, heavy rain can cause rising waters and flooding. This water is loaded with contaminants and even fecal matter containing bacteria, viruses and parasites that can make people sick.

“And talking about kids, you know, they’ll go out and play in that stuff,” Curtis said.

Adults, too, have been seen kayaking in Charleston’s floods.

The CDC said contaminants in water can lead to reproductive problems, neurological disorders and gastrointestinal illness. According to the World Health Organization, diarrheal illnesses are the second most common cause of death worldwide in children under age 5.

Extreme rainfall creates a flushing mechanism for anything that is on the ground. It often flushes pollution into water bodies, water systems and estuaries. And a contaminated water source could mean a shortage of clean drinking water.

There are billions of people worldwide who lack access to safe drinking water, which makes them higher risk for waterborne illness.

Guilkey said in North America the most waterborne disease outbreaks occur after extreme precipitation events. About 7.3 million Americans get sick every year from diseases spread through water, the CDC said.

Many of the needed climate solutions to protect the Earth can also make people healthier. For example, decreasing greenhouse gases doesn’t only address climate change. But considering more efficient options like biking instead of driving decreases a person’s risk of heart disease and diabetes, Guilkey said.

And while long-term exposure to nature can increase life’s satisfaction, outdoor green spaces are often cooler than city blocks and can prevent flooding.

Individual action is important, but large-scale, aggressive policies can help mitigate climate change, Guilkey said. And creative solutions might assist folks in adapting to the changing climate.

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston

The Citadel’s Swain Boating Center provides popular event space for Charleston The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair

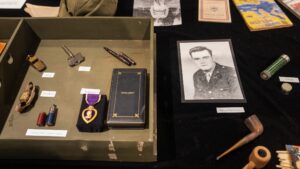

The Citadel Board of Visitors reelects chair The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day

The Citadel Museum honors alumnus killed on D-Day