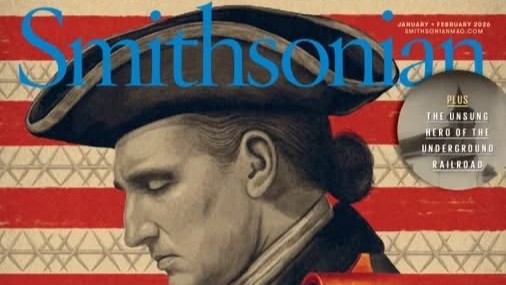

The following in an excerpt from article written by David Preston, Ph.D., that appeared in the January/February issue of the Smithsonian magazine. Preston is the Gen. Mark W. Clark distinguished chair of history and director of the master’s program in military history.

By David Preston, Ph.D., General Mark W. Clark Distinguished Chair of History and Director of the M.A. in Military History

A Skirmish Early in George Washington’s Military Career Helped Define Him. It Could Have Killed Him

For the rest of his life, George Washington would remember the chaos and tragedy of November 12, 1758. At 26, he was the colonel commanding the Virginia Regiment, a British subject fighting for his king in the conflict now known as the French and Indian War. The soldiers were advancing westward in a campaign to take the Ohio Valley from the French and their Native allies. The troops had crossed the Appalachians and built a fort called Loyalhanna in what is now western Pennsylvania—about 50 miles east of Fort Duquesne, the strategic French outpost they planned to conquer.

In the October 2019 issue of Smithsonian, I wrote about a 1754 document I discovered in the British National Archives: an eyewitness account from an Ohio Iroquois warrior who identified Washington as having fired the first shot in the skirmish that sparked the war. Now, as British troops closed in on the Ohio Valley, Washington was about to play a key role in the conflict’s end.

On that Sunday in November 1758, the British commander, General John Forbes, got word that a French and Indian scouting party was approaching Loyalhanna. After he sent a unit of Virginians into the woods, the roar of muskets was loud enough that Forbes sent Washington out with reinforcements. In the dusky light and confusion, each of the two Virginia parties mistook the other for the enemy. The skirmish would come to be known as the “friendly fire incident,” and Washington was largely responsible for restoring order. He placed himself between the two Virginia units, knocking the soldiers’ muskets upward with his sword and commanding them to stop firing. By the time the shooting ceased, as many as 16 Virginians were dead and more than 20 others were wounded. Washington came out unscathed, but in his orderly book, he noted that as his soldiers marched out the next morning, they were to “carry a proportion of spades in order to [bury] the dead.”

Thirteen days later, the British captured Fort Duquesne and, with it, control of the Ohio Valley on Virginia’s western frontier. But Washington remained haunted. In 1787, jotting down his personal reflections for a biographer, the soon-to-be president wrote that his life had never been “in as much jeopardy…before or since” that moment in the Pennsylvania woods. By that time, everybody knew about Washington’s courage during the Revolutionary War. In 1776, he’d led 2,400 men across the Delaware River as sleet rained down and ice floes drifted past in the darkness. But at Loyalhanna, Washington wrote, he’d faced “more imminent danger.”

Looking ahead to the major events of 2026-27

Looking ahead to the major events of 2026-27 Upcoming News from The Citadel – February 2026

Upcoming News from The Citadel – February 2026 Cadets and students named to The Citadel’s fall 2025 dean’s list

Cadets and students named to The Citadel’s fall 2025 dean’s list