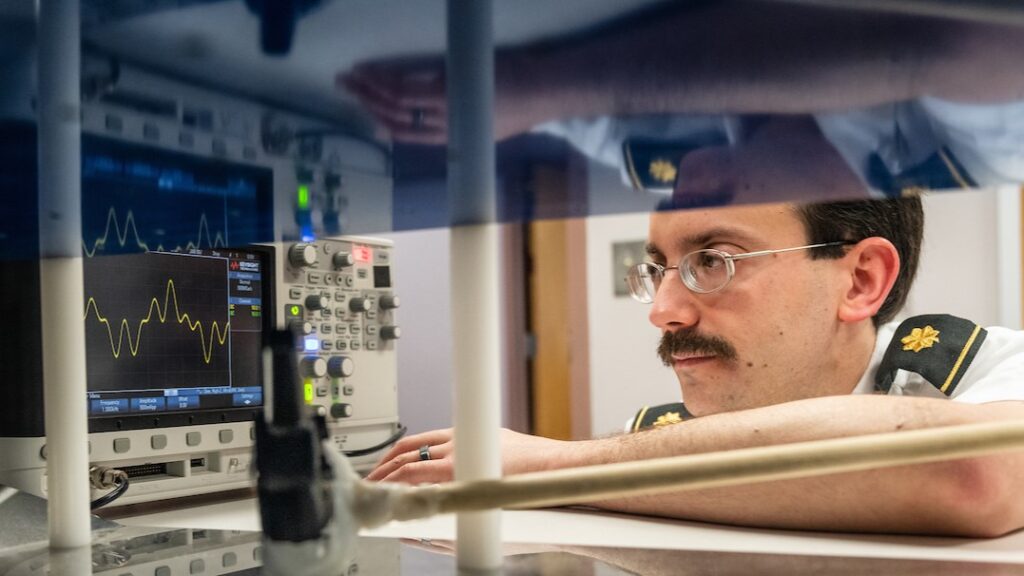

Photo: Greg Mazzaro, Ph.D., works with his invention, a prototype device designed to detect IED triggers.

As seen in The Post and Courier, by John Ramsey

In the hunt for buried bombs, researchers have deployed bacteria and bees, giant rats and German shepherds. The Navy trains bomb-detecting dolphins.

Soldiers assigned to road patrol duty in Iraq and Afghanistan often performed one of the world’s most dangerous jobs equipped with metal detectors and vehicles built to survive an explosion. There was a catch too: Look down to where the bombs might be buried and risk getting shot in an ambush. Look up, scanning the horizon for threats instead of the ground, and risk getting blown up.

Over the last two decades improvised explosives became one of the most effective weapons of war, killing more than 3,300 coalition troops in Iraq and Afghanistan and injuring thousands more.

A professor in The Citadel’s electrical and computer engineering department is working with Army researchers on a new way to help soldiers see the unseen before it’s close enough to kill them. His theory, proven in lab experiments, relies on a combination of radio waves and sound waves to detect certain metals like cell phone parts that are often used to trigger the bombs.

When police point a radar gun at a moving car, the machine calculates how fast the car is going based on the way the radar waves compress as they bounce back.

Finding bombs this way relies on the same concept, with a twist. In Vietnam, radar waves helped soldiers spot enemies through thick jungle foliage. But the technology struggles with small components the size of bomb triggers. And in the speeding car scenario, the device can’t tell a car apart from a tree unless the car is moving. Buried bombs don’t move before exploding, unless you can find a way to shake them.

That’s where the loudspeaker comes in. Soundwaves penetrate the ground. Think of the vibrations as a car with thumping bass approaches from a distance.

Those vibrations can move metals just enough for radar waves to spot them.

In a demonstration of the concept, professor Gregory J. Mazzaro places a radio in a small box equipped to produce electromagnetic and audio waves. Turning on the radar alone reveals nothing. Neither does just the sound. But use them together, and two new peaks appear on the chart showing the waves. And there it is.

The hidden object lies in those two peaks, and the waves help flush out its precise location.

In theory, soldiers would know from a safe distance to avoid that patch of dirt or call in a bomb squad.

“If you listen with the antenna, you’ll actually receive the mathematical combination of both the acoustic wave and the electromagnetic wave,” Mazzaro said. “This technology is one way to see what’s out there that we otherwise couldn’t with our own eyes detect.”

Mazzaro’s patented method is years from being developed into a device soldiers can use on the battlefield.

Even then, it depends on whether demand remains: Will bombs be buried in the next war, or flown into battle on small drones? Will another technology work better or cross the finish line into development sooner?

The Pentagon has poured billions of dollars into finding answers. And researchers around the world are testing novel ideas. Maybe the superior smelling sense of dogs, rats or bees could be useful. Maybe a laser shot across an open field would reveal the location of gases emitted by explosives, or a thermal camera will show spots where the soil was recently disturbed. Or a robot with slender fingers will dig into sand to find objects underneath.

‘“There’s all sorts of different technologies that people use or have tried to use over the years,” Mazzaro said. “None of them have solved the problem to such an extent that they’ve ever told us, ‘We got it. We’re done. We’re good.’”

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit The Citadel’s presidential search committee announces four finalists

The Citadel’s presidential search committee announces four finalists Prestigious Cincinnati and MacArthur awards presented to Citadel cadets

Prestigious Cincinnati and MacArthur awards presented to Citadel cadets