As seen in The Post and Courier, by Paul Bowers

James Bezjian returned from Scotland in December with a trove of Bronze Age and Byzantine artifacts stashed on a hard drive.

A sculpture of a woman with a bowl in her lap, a tiny coin bearing the face of Medusa, and dozens of other antiquities were preserved in minute digital detail by a three-dimensional scanner.

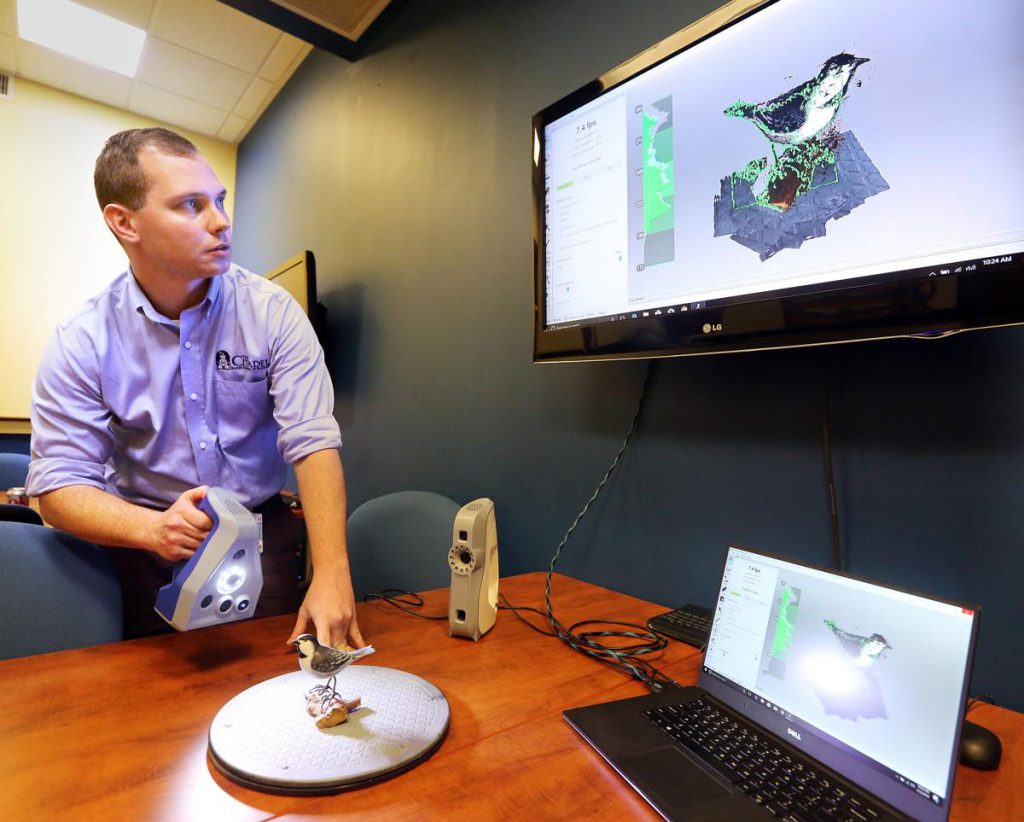

Bezjian is the director of the Innovation Lab at The Citadel’s Baker School of Business. He spent 12 days testing out the new scanners on artifacts held by the University of St. Andrews. After getting the hang of the devices and capturing some sharply focused 3D images, he plans to teach undergraduate students to use them in the field this semester.

The first class of six students in the new Innovation Lab class will take their scanners to two sites: The Charleston Museum and the Army Airborne and Special Forces Museum at Fort Bragg in North Carolina.

“The beauty of this class is that, unlike most of the classes at The Citadel, it’s not systemized. There is open and ripe opportunity for them to create and conceptualize whatever they want,” Bezjian said.

3D scanning technology is not new. The idea made headlines in 2015 when student researchers launched Project Mosul, seeking to scan and preserve the world’s irreplaceable artifacts after ISIS radicals demolished a sixth-century Christian monastery and laid waste to the Mosul Museum in Iraq.

Bezjian said The Citadel spent about $30,000 of donated funds for its two portable Artec scanners. Letting smaller institutions use these tools was always part of the mission, he said.

“I saw this lab as an opportunity to reach not just locally, nationally, but globally,” Bezjian said. “It allows us to be very mobile with our technology and far in our reach.”

3D scanners are still out of the price range for many smaller institutions like the Charleston Museum, according to Matthew Gibson, the museum’s curator of natural history.

“Partnerships like this with The Citadel are basically how we’re able to use this technology,” Gibson said.

This marks the second such partnership the Charleston Museum has entered. Gibson previously hosted students from the New York Institute of Technology in December 2016 who mainly scanned whale fossils from the Oligocene epoch.

The museum now displays interactive views of those scanned artifacts for free on its website. Some are even downloadable, so students around the world can use the files to create replicas on a 3D printer.

It’s a fun tool for teachers and the idly curious, but Gibson said the main purpose is to make the images available to researchers. Now scientists looking to study ancient whale species like the Agorophius pygmaeus can get a painstaking preview of what’s available — and sometimes find all the information they need — before booking a flight to Charleston.

At the Army Airborne and Special Forces Museum, Bezjian said students will be scanning fragments of the Black Hawk helicopters that Somali militia members shot down in the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu — the incident that inspired the book and movie “Black Hawk Down.”

Once students get the hang of the scanners and the software used to sharpen the images, Bezjian said, the sky is the limit. He said he hopes to one day travel to Jordan and take images of artifacts there.

“The goal of this is unite as many fronts as we can to come up with new ideas and solve problems,” Bezjian said.

MUSC, Citadel collaborate on health innovation initiative

MUSC, Citadel collaborate on health innovation initiative Citadel professor receives Army commission to restart new ‘Monuments Men’ mission

Citadel professor receives Army commission to restart new ‘Monuments Men’ mission Past and future meet in a plastic present

Past and future meet in a plastic present