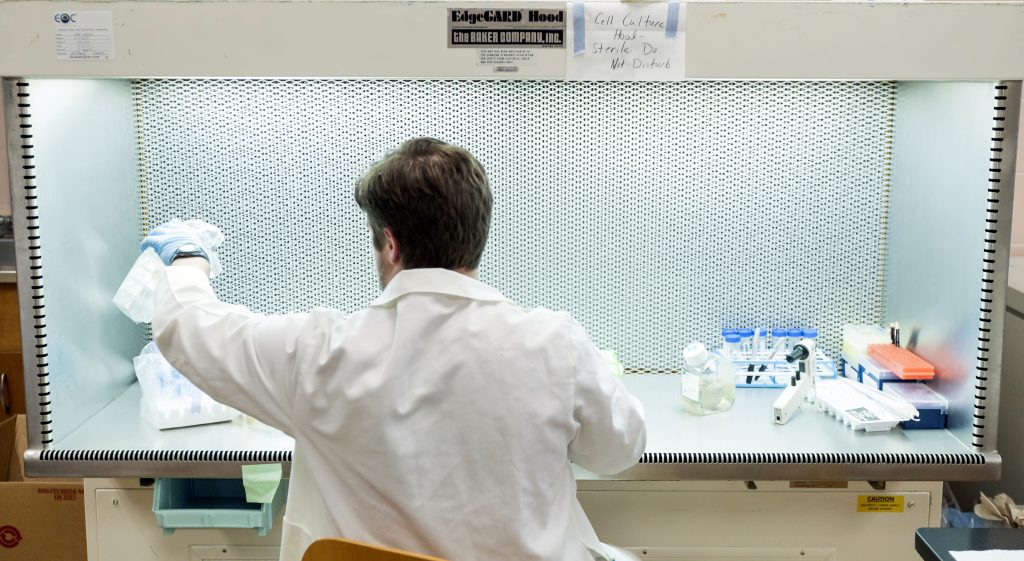

Citadel professors, cadet researcher verifying protein movement that kills unhealthy cells

A living cell has thousands of internal parts. The movement of one of those parts, a naturally occurring protein, is at the center of a decade-long research effort led by Citadel biology Professor Kathy Zanin, Ph.D.

“Some cells are doomed. They are going to die due to developmental stages, mutations, stress, or other errors that they cannot correct. When a process called apoptosis helps them kill themselves off, healthy cells are better protected,” explained Zanin.

“What we are studying in our lab about one part of this process could influence human health science. But, because it is contrary to current scientific dogma, we must generate enough evidence to convince the scientific community.”

Cadet John DeStefano, a biology major hoping to become a doctor, is an undergraduate researcher paid to collect the evidence.

“This is a big deal. Our cells are coping with stress brought on by certain diseases such as cancer, in a way we didn’t know before. Understanding how this process works could lead to new ways for us to manage these diseases,” DeStefano said.

With the help of Citadel microbiologist Claudia Rocha, Ph.D., Zanin and DeStefano worked to convince other scientists that a cellular protein, Histone H3, moves from the nucleus to the powerhouse of a cell, the mitochondria, which regulates stress responses. This fuels the suicide of an unhealthy cell, helping healthy cells thrive.

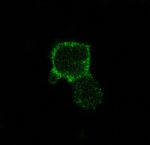

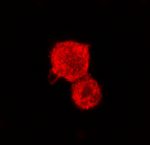

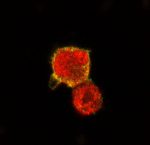

Look at the proof, courtesy of Rocha. She uses immunofluorescence, a technique using fluorescent dye, to label the cell parts with different colors to identify their locations and interactions. “We labeled the Histone H3 with one color and the mitochondria with another color. Under the microscope we can see exactly where they overlap because new colors are generated,” Rocha explained. “People can’t say it isn’t true when we have real images of it happening.”

Micrographic A: the blue shows the nucleus only

Micrographic B: the green shows the mitochondria only

Micrographic C: the red is the Histone H3 protein only

Micrographic D: shows the colors changing to yellow when the red and green (mitochondria and Histone H3) overlap

The final micrograpic shows that Histone H3 is merged with the mitochondria, which Zanin says supports their hypothesis that Histone H3 may help control apoptosis by communicating with mitochondria.

“We have verified this activity in cauliflower, fruit flies, cow liver, and now in human cells,” Zanin said. “But we must gather much more proof before our discovery will be accepted by scientific journals.”

DeStefano is determined to help make it happen. He can focus exclusively on his research while classes are not in session because he is paid through The Citadel Summer Undergraduate Research Experience.

“I am fortunate to be doing this important work with my mentor, Dr. Zanin. I couldn’t have committed to if it weren’t a paid research opportunity because I needed summer income,” said DeStefano.

DeStefano says he is becoming more scientifically literate, and even more passionate about human health sciences. “I’d encourage other young scientists to pursue undergraduate research jobs, paid or unpaid. It is the best way to discover if what you think you want to do for a career is really what you should do.”

The Citadel celebrates Cybersecurity Awareness Month with engaging campus events

The Citadel celebrates Cybersecurity Awareness Month with engaging campus events My Ring Story: “The Citadel has taught me that I can do much more than I think I can do”

My Ring Story: “The Citadel has taught me that I can do much more than I think I can do” My Ring Story: “This ring is more than a symbol, it carries stories of hard work, resilience and the hope of those who came before me”

My Ring Story: “This ring is more than a symbol, it carries stories of hard work, resilience and the hope of those who came before me”