As seen on Quilliaminternational.com

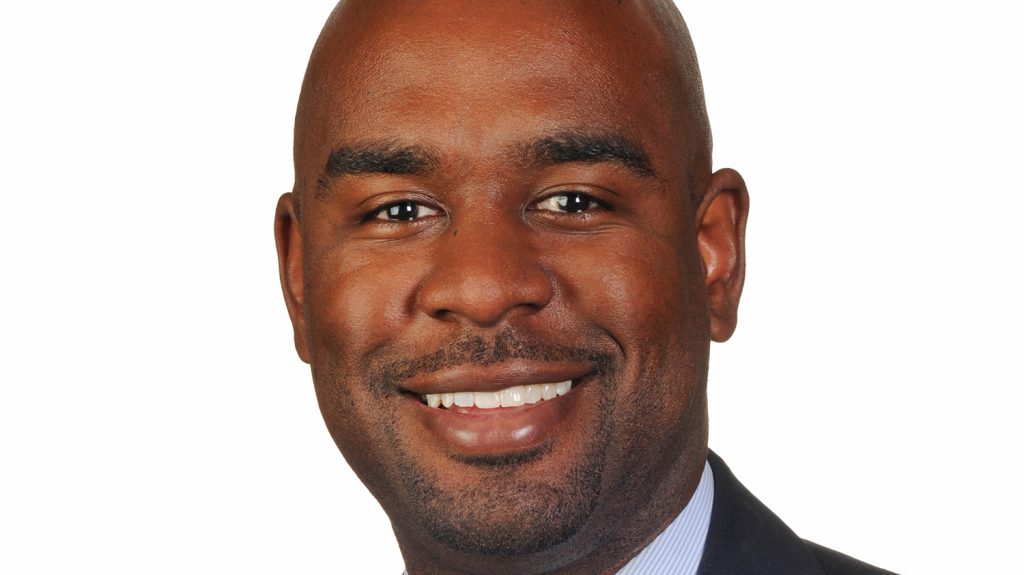

By Dr. Muhammad Fraser-Rahim, Executive Director, North America for Quilliam International and Professor of Intelligence and Security Studies at The Citadel.

This week’s terrorist attack in London by Usman Khan shows yet again why the international community must remain more vigilant than ever against extremism. Khan himself was previously convicted and sentenced to 16 years for plotting to blow up the London Stock exchange and was deeply inspired by the American ideologue, Anwar Al Awlaki.

Furthermore, during his incarceration, he claimed to have undergone a process of reform, stating that he was “immature” when he committed the offences for which he was imprisoned. He expressed a desire to engage in a process that would allow him to leave extremism. As is now clear, Khan was neither sincere nor actually engaged in the highly complex process of disengagement, deradicalization and rehabilitation.

Quilliam, the organization in which I work, understands these concerns all too well. We were established by former Islamist extremists who know that the journey in and out of extremism is not something that happens overnight. It is a slow, long, hard process, which is not for the faint hearted.

There are too many practitioners, policymakers and academics who advocate a quick fix approach to deradicalization and rehabilitation. I recall one conversation earlier this year with a leading American academic with a distinguished reputation in relation to matters of extremism and terrorism. I was somewhat surprised to hear him argue that the business of working one-on-one with individuals, to guide them out of extremism, “takes too long”. He didn’t see much value in our efforts and approach. He was not personally willing to roll up his sleeves and get stuck in to the arduous, time-consuming business of coal-face anti-extremism work with those who present risk to our fellow citizens.

So, what can be done?

All over the world, countries such as Denmark, UK, Saudi Arabia and Singapore have been experimenting with a range of approaches to aid individuals in their transition from extremism. These myriad strategies and approaches include utilizing cognitive development, community re-integration, ideological reform and mental health counseling.

I spent a decade working as a counter-terrorism officer for the National Counterterrorism Center in Washington, DC during which I traveled all over the world, including a stint in Guantanamo Bay talking with extremists. This experience has given me a strong sense of the dynamics of the problems we now face.

We in the United States now understand that it is essential to develop a response to the full spectrum of threats presented by the multitude of terrorist groups which operate in our societies. The FBI and social scientists are now fully aware that domestic terrorists – including while males determined to carry out acts of violence – present a threat as significant as Islamist extremists like al-Qa’ida or ISIS. The horrific white nationalist terror attack in New Zealand which left 49 Muslim worshippers dead is the most recent example of the challenge we now face. Domestically, in the United States, a salient example is provided by the Coast Guard Lieutenant, Christopher Hasson, who stockpiled weapons, hoping to eventually use them to establish a “white homeland”. Hasson created a digital spreadsheet identifying House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, as well as other high ranking Democrats, as targets.

All of this raises the question of how we should respond to the danger that is posed by terrorists both at home and abroad. What common threats do these groups present? How does the US, as a nation, come up with appropriate measures in relation to the work of prevention, rehabilitation and reintegration?

The US has relied on a range of strategies to prevent radicalization but has rarely taken stock of, let alone utilized, the unique skills of individuals who are or have been involved in extremist activity to deradicalize others. The focus has always been on prosecution and punishment. Partisan politics represents a formidable obstacle to the formation of organized off-ramping programs, such as those which take place in the UK.

At present, we have no uniform and comprehensive deradicalization program. Rather, there are a small number of organizations who have engaged with this issue. Organizations like Free Radicals and Take Charge seek to create opportunities to divert individuals from extremism and associated violent conduct. For example, Take Charge has developed a comprehensive program targeted at individuals susceptible to the influence of drugs and gangs.

As the US seeks to come up with the best approach for deradicalization programs, now is the time to take stock. We should determine which efforts are working, in communities throughout the world. Quilliam has developed multifaceted strategies on rehabilitation based on the insights we have gleaned from the many years we have spent addressing the threats presented by a range of extremist groups and individuals. Our VICE news documentary published last year follows the deradicalization process of the youngest person in US history, Mohammed Hassan Khalid. Extrapolating from the knowledge and experience of our colleges in the United Kingdom, and incorporating the best of other rehabilitation programs that have been effective in the US, we produced a unique and tailored approach toward Khalid’s journey out of extremism.

Any long term and sustainable deradicalization program in the US must draw upon existing efforts and experiences from across society. A multidisciplinary approach which includes civil society, religious, governmental and lay communities is central to success.

Deradicalization is essential work. Organizations like Quilliam are needed more than ever in light of the attacks in London.

Meet the South Carolina Corps of Cadets leadership for 2026-27

Meet the South Carolina Corps of Cadets leadership for 2026-27 The Citadel prepares for Recognition Day and Corps Day

The Citadel prepares for Recognition Day and Corps Day How an ROTC program at The Citadel is shaping the Army’s next generation

How an ROTC program at The Citadel is shaping the Army’s next generation