Note: This article was a popular piece when it was first shared on The Citadel Today in Nov. 2018. We are sharing it again now, ahead of Memorial Day.

As seen in the Charlotte Observer, by Bruce Henderson

When dark falls, the people of a Matthews neighborhood listen for the lonely military call that signals a days’ end: A bugler playing Taps.

“I keep track of what time the sun goes down, step out on my front porch and play,” said former Army Reservist Don Woodside. “If I forget to play, I get phone calls from neighbors — ‘Are you sick?’”

There are stories within the story, this Veterans Day, of Woodside’s bugling. They’re tales of loss and remembrance that begin before World War II, recount the tears shed for a father’s sacrifice and are still playing out today.

Woodside, 77, is a volunteer with Bugles Across America, which offers players to perform Taps at the funerals of military veterans. He also sometimes sits at the Mecklenburg County Vietnam Veterans Memorial, playing into the long, granite arc to magnify his horn’s sound.

He does this to honor all those who served, but one in particular: his late uncle, Milton Woodside, a Charlotte native and World War II fighter pilot who survived more than three brutal years as a prisoner of war in Japan.

After his 1940 graduation from The Citadel, the Charleston military college, Woodside had entered flight school with the Army Air Corps and become a pilot of P-40 Warhawks, a single-engined fighter plane. In the summer of 1941, the young second lieutenant was stationed at Clark Field in the Philippines with the 20th Pursuit Squadron.

The Japanese attacked Clark a day after they hit Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941. Most planes at the airfield were destroyed, but determined crews managed to salvage a few P-40s. Woodside was among the pilots who continued taking off from the bomb-cratered runway to fight the Japanese.

“Fill it up, I’m going back up,” Don Woodside recalls his uncle saying in recounting one mission.

That was after the war, when Milton Woodside had returned home and become administrator of what is now Sampson Regional Medical Center in Clinton. The former pilot often returned to Charlotte to visit his parents and stayed at the Eastover home of Don Woodside’s family. That’s where young Don gleaned what little his uncle had to say about the war.

“You had to pull it out of him,” he said.

Milton Woodside’s oldest son, M.H. “Woody” Woodside, 71, is himself a 1970 Citadel graduate who spent 22 years with the Georgia Army National Guard. Now president of the Brunswick-Golden Isles Chamber of Commerce, he regrets that he was never able to have long talks about the war with his father before his death in 1973.

Histories of combat in the Philippines flesh out his dad’s wartime experiences.

Woodside was flying without ammunition after managing to take off from Clark Field when two Japanese Zeros attacked him from behind near Manila, according to “Doomed at the Start,” a 1995 account of U.S. pursuit pilots in the Philippines. Once his plane’s instrument panel was shattered, the book said, Woodside put his plane into a steep dive and bailed out.

That happened on Dec. 10, 1941, Woody Woodside said. His father had parachuted into friendly territory.

But as Japanese ground forces closed in over the following months, the U.S. abandoned Clark Field and retreated to the southern Bataan Peninsula before surrendering in April 1942.

The forced 65-mile march up the peninsula of thousands of sick, hungry prisoners, including Woodside, became World War II lore. About 600 Americans and at least 5,000 Filipinos died on what became known as the Bataan Death March, according to Army history.

Milton Woodside’s vivid account of the march, apparently drawn from a post-war debriefing, is quoted in “Deadly Sky,” a 2016 book on American combat airmen in World War II by military historian John McManus. Japanese soldiers severely abused their prisoners, he recounted, denying them water and at one point clubbing him for hiding a small can of beans.

“Any prisoner becoming exhausted and falling out was either shot or bayoneted,” Woodside says in that telling. “An Air Corps 2d Lt. marching next to me became exhausted and could go no further. Unable to carry him, I helped him over behind some bushes to lay down. The follow-up … guard saw us and motioned for me to go on. I left the man my canteen of water and moved on. About 100 yds. on, I looked back to see the guard repeatedly bayoneting the sick man in the chest.”

An Army history says the “deliberate and arbitrary cruelty of some of the guards led to many of the deaths and immeasurably increased the suffering of those who managed to survive.”

A POW in Japan with hidden gold

Woodside was held prisoner for nearly 3 1/2 years at the Umeda prison camp in Osaka, his son said. Because of his rank as an officer — fellow prisoners fashioned crude aviator wings for him — the Japanese put him in charge of the 40 to 50 other prisoners in his hut.

Prisoners of the Japanese endured hellish conditions. Apart from disease and starvation, an account by the Army’s Center of Military History says, prisoners “had been beaten and kicked, had been forced to bow and to obey endless petty rules invented by their captors.”

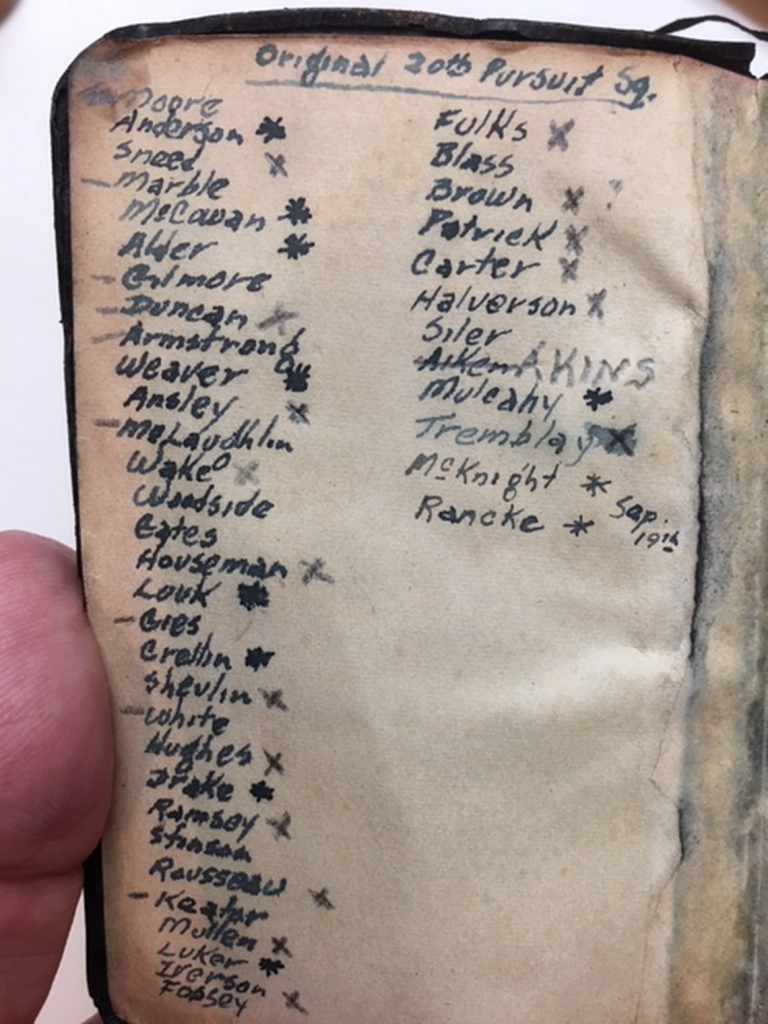

“I still have his military-issue Bible with names of all 20th Squadron folks with asterisks by them — most had asterisks, for death — that he carried with him while in prison,” Woody Woodside said.

His father clung to one other possession, one that he had hidden away: his gold Citadel class ring.

When conditions turned dire, the former POW later told his nephew, he traded it to a Japanese guard in exchange for food and water for his fellow prisoners.

In August of 1945, relatives say, Woodside also witnessed the mysterious glow on the horizon of the two U.S. atomic bombs that ended the war.

He’d spent much of his years as a prisoner digging coal in Japan. As U.S. troopers freed the prisoners after Japan’s surrender, Woodside snatched up a grim prize: the battered bugle that guards had used to wake up their prisoners each morning.

A phone call from the Philippines

In 1953, back in North Carolina after a hero’s welcome home and beginning his career in hospital administration, Milton Woodside got a surprise call one day from the Philippines.

The caller was an American who come across a Citadel ring, class of 1940, engraved inside with the initials MHW, in a pawn shop. The man had contacted The Citadel for help in identifying and locating the graduate.

“He said, Mr. Woodside, did you have a Citadel class ring that you lost in the war? I jumped up screaming and said, how much do you want for it? He said, just give me your address” and mailed it back, Don Woodside recalled his uncle saying.

That’s how the ring came home.

Woody Woodside had lost his own Citadel ring a few years after graduating in 1970. He started wearing his late father’s ring.

But he’d never known its history until four years ago, when he visited his cousin Don for the Belk Bowl football game between Georgia and Louisville. The two visited Charlotte’s Louise Avenue, where Milton Woodside had grown up. For the first time, Don Woodside relayed his uncle’s tale of the lost and found ring.

“At the end of the story, I said, ‘I wonder what ever happened to that ring?’” Don Woodside said. “He said, look here — he pointed to his right hand and, boy, the tears came.”

Woody Woodside: “Don told me the story that I never knew. It makes it even more meaningful, and I’m very grateful. I guess that the greatest generation is about gone, and amazingly enough not that many talked that much about it. They went about their lives.”

Play Taps with honor and reverence

That’s the story of the gold ring. The other story, of Don Woodside and his bugling, continues each day at sunset.

At 5:25 p.m. Wednesday, dressed in Army dress blues, Woodside stepped onto his front stoop beside the flag that flies there. He lifted the bugle in his right hand and, stock still, played the haunting melody into the setting sun.

The notes came out slow and stately, and that’s for a reason. Woodside had auditioned for Bugles Across America by phone about a year ago, and almost didn’t make the cut. He played Taps too fast, his interviewer said. Try again.

“I play it with ‘honor and reverence,’ were the words I think he said,” Woodside said.

He had previously played the flugelhorn, which resembles a trumpet, during his daily Taps renditions. On Wednesday he blew another instrument for the first time.

It had arrived in a package that day from his cousin Woody: the battered old bugle his uncle had liberated from the Japanese captors in 1945.

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit Looking ahead to the major events of 2026-27

Looking ahead to the major events of 2026-27 Photos from campus: January in review

Photos from campus: January in review