As seen in Quilliam International, by Dr. Muhammad Fraser-Rahim, executive professor of Quilliam International and assistant professor at The Citadel

The diverse religious experience of African Americans in the US stretches from the first arrival in the southern United States of slave ships bearing Muslim slaves from West Africa to the strong religious convictions of the American-born black church. Together, African Americans have created spaces of peaceful coexistence while at the same time providing constructive critique using religious and lawful frameworks, to promote inclusion, pluralism and peace. Extremist groups like ISIL and al-Qa’ida have tried and failed to court disenfranchised populations and play on the grievances of the African American community, from upheavals in Baltimore and Ferguson. African Americans have provided a lesson in how to combat extremism: both domestic and international.

I am a native of Charleston, SC born and raised. Both sides of my family trace their family heritage to Charleston and Georgetown, SC. My ancestors comprise five generations of college educated teachers and Christian pastors. My family were educated and raised in the South with a deep belief in God, faith and country. My parents, like many African Americans in the 50’s and 60’s, were deeply affected by the social and political conditions of African Americans in the United States. As a result, my parents separately converted to Islam in the early 60’s in the United States to Islam and shortly thereafter met each other, and married.

My extended family, and many of my friends attend Emmanuel AME church, where in 2015 Dylann Roof murdered nine African Americans. I share with them the deep sense of loss that that this horrific crime occasioned. When news of the tragedy broke, I couldn’t help, but think of the reaction of my friends, South Carolinians and Americans at-large if the crime had been committed, not by a white supremacist, but by a gunman yelling “Allahu Akbar”. Many would have had similar thoughts, when the massacre was first reported. Some may have initially concluded that the attack had been conducted by ISIL, al-Qaida or another Islamist terrorist group.

However, the experience of my family provides another perspective. For many African Americans, converting to Islam was not an uncommon move. In the late 50’s and 60’s, many of us embarked on a search for spiritual and religious clarity which took some to Islam, and others to other religious and social movements. For my parents in particular, conversion was not a denial or rejection of Christianity. Indeed, they respected and valued their Christian heritage. They acknowledged that, without the Abrahamic tradition which we share with both our Jewish and Muslim brothers and sisters, they wouldn’t be who they are today.

I was raised in Charleston and attended schools in that city. In the evenings and weekends I attended Islamic school, where I read and memorized the Qur’an in Arabic and was taught Islamic history. For me, Islam was both uniquely and authentically American and a vital component of the African American Muslim experience. The education that I received at the Islamic schools in Charleston wasn’t delivered by teachers from Saudi Arabia or even the great Islamic centers of learning in Africa. They were men and women, hard working Americans who had converted to Islam, some as far back as the early 30’s: and all of them from the United States.

Growing up Muslim, what we understood was this. Islam is not, and should not be seen as foreign in the United States. It is, in particular, native to Charleston. Most scholars estimate that between 20-40 percent of enslaved Africans who came to the United States came from Muslim societies in West Africa. We now know that the early founders of the United States – including Thomas Jefferson and George Washington – observed and studied the Islamic canon and Muslim civilization in order to develop a deeper understanding of a multi-ethnic and pluralistic society that respected all people. Nobody would argue that either statesman was perfect. Their process of moral and intellectual development might be described as a work in progress. Notably, Thomas Jefferson himself enslaved Africans who, as far as can be ascertained, were from West Africa and therefore likely of Muslim heritage.

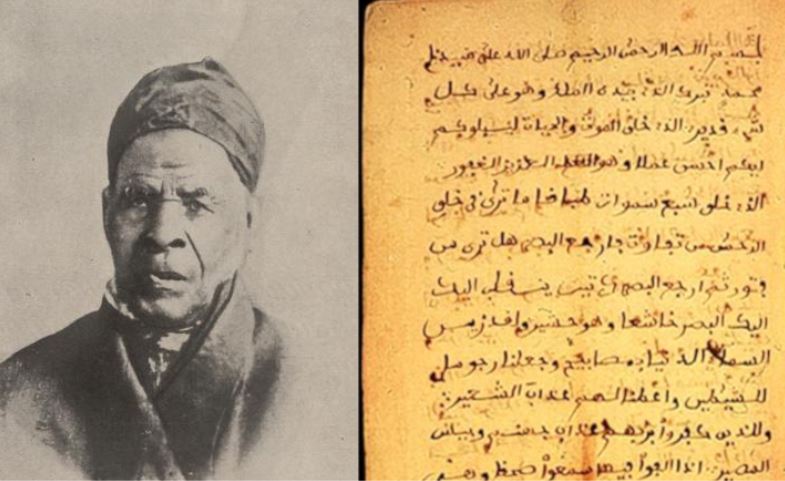

I have always been fascinated by the story of the Senegalese-born Omar ibn Said, who arrived in in Charleston, SC in 1807. Ibn Said was deeply rooted in Islamic spirituality and Arabic language, and arrived to work on the rice plantations. Fleeing an abusive slave master, ibn Said arrived in Fayetteville, NC where he was eventually placed in jail. Literate in Arabic – his second or third language – ibn Said produced fourteen manuscripts from memory in that language. His legacy is the account of the plight and condition of being a slave, the treatment he faced in America, and most importantly Islamic verses of protection which assisted him in surviving peacefully and non-violently in the American South.

It is that spiritual and reflective form of Islam that ibn Said learned in West Africa that was transmitted, and lives on in many of his descendants, and those of other enslaved African Muslims, who lived through the antebellum period in the US. The majority of African Americans today are members of the Christian faith which was adopted through a process of conversion and acculturation. Over time, both Islamic and African traditional religions dispersed, and in some ways reformed in the humid air of the Southern United States. The majority of African Americans today who converted to Islam in the 50’s and 60’s saw themselves as re-adopting the faith of their ancestors as a way to connect back to a tradition. On occasion, original traditions and practices survived, such as Gullah/Geechee traditions of the South Carolina Lowcountry. All were, in essence, an attempt to preserve the connection to their African ancestry.

The story of Emmanuel AME church demonstrates the power of that legacy. It is an attitude, a way of seeing the world, which stretches across the diverse faith based traditions of African Americans. In the immediate moment and aftermath of the events at Mother Emmanuel, the African American community didn’t retaliate, but instead used their religious and spiritual tradition to serve as both a source of personal strength and as an example to others. Even at this time of immense tragedy, the larger African American community – Muslim, Christian or other – called their aunt, uncle, cousin and fellow relative to check on one another. They found a voice of peace and tolerance.

The example of restraint, love, forgiveness and respect serves as an example domestically and abroad. It is that response which provides us with a model for those who seek to counter violent extremism throughout the world.

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine

Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine Citadel professor to serve as next Inspector General for the U.S. Department of Defense

Citadel professor to serve as next Inspector General for the U.S. Department of Defense