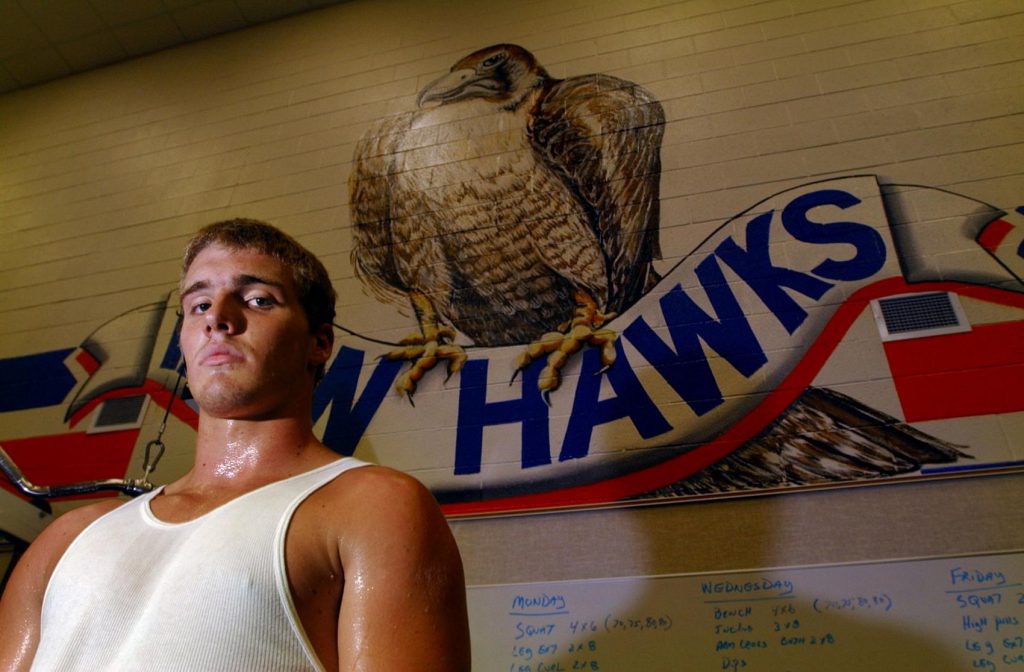

Photo: Special Forces Capt. Ben Carnell, a former Citadel quarterback, was wounded a year ago while serving in Afghanistan (Courtesy: Grace Beahm Alford, The Post and Courier)

As seen in The Post and Courier, by Jeff Hartsell

Sometime in the midnight hours of April 3, 2019, Special Forces Capt. Ben Carnell was loaded onto a gurney outside a mountaintop village in Afghanistan.

A tourniquet was wrapped tightly around his upper left thigh. It choked off the flow of bright-red femoral blood from three bullet holes in his leg; a fourth bullet had nicked his calf, a fifth dented a magazine strapped to his side and a sixth sliced through a night-vision cable attached to his helmet, just inches from his brain.

Carnell could hear the battle against ISIS-K fighters raging around him. But he couldn’t see. His vision was scrambled by the detonation of an IED, which exploded nearby seconds after he was shot.

A buddy grabbed his hand and Carnell croaked out a joke.

“Hey, I punched that ticket, didn’t I?” he said.

Less than a year after he faced death on that mountainside in eastern Afghanistan, Carnell looks back in wonder.

“I can honestly say it was the best night of my life,” says the 2009 graduate of The Citadel and former Bulldogs football player. “I knew I was right where I was supposed to be, doing what I was supposed to do.

“It was worth every minute and I’d certainly do it again.”

9/11 and The Citadel

Since Sept. 11, 2001, almost 7,000 U.S. troops have been killed in combat and almost 53,000 wounded, according to the Congressional Research Service. Many of them were galvanized to serve by the events of 9/11, when almost 3,000 people were killed by terrorist attacks on New York City, Washington, D.C., and a jetliner that was forced down in a Pennsylvania field.

On that fateful day, Carnell was sitting in Ms. Cox’s ninth-grade Spanish class at First Baptist School when the principal stuck his head in the door.

“I’ll never forget it,” said Carnell, who is 32. “He said a bomb had gone off in New York City.”

As the day unfolded, Carnell and his classmates watched on TV as the events of 9/11 became clear — a terrorist attack on the World Trade Center towers.

“As a young man, I was angry that they had hurt my people intentionally,” he said. “But I didn’t really know what to do about it.”

There wasn’t much a high school freshman could do, but that feeling stuck with Carnell as he completed a standout football career as a quarterback at Hanahan High School, then went on to The Citadel.

“I thought tough men played football,” he said. “And I thought tough men went to The Citadel.”

As a freshman at The Citadel in 2005, Carnell was a fourth-team backup behind starter Duran Lawson. When Lawson was injured early in the season, coach Kevin Higgins turned to a couple of other backups before Carnell. The Bulldogs lost five straight games, but Carnell started the final two games of the season and led them to victories over Elon University and Virginia Military Institute.

When Lawson returned in good health the next season, Carnell was moved to tight end and special teams. As a senior, he had to give up football because a neck injury made it too dangerous for him to play.

“After I hurt my neck, it was not clear how I would get in the Army or if I would,” he said. “I went to work as a carpenter, and in 2009 the economy was not awesome. My dad needed some help with his company, so I did what I thought I was supposed to do and went to work for him.”

But as the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq wore on in the aftermath of 9/11, he felt a different calling. Ben often talked to his girlfriend (soon to be his wife), Beverly Harris, about his feelings. She was the sister of one of his classmates in Tango Company at The Citadel, and had played college basketball at Transylvania University in Lexington, Ky.

“In the conversations you have as a young adult, about politics and the world, there were things I felt strongly about,” Carnell said. “And Beverly told me, ‘If you feel strongly about these things, you probably should act on them.’”

‘Last 100 yards’

When the recruiter at the Army National Guard said he could get Ben into basic training by the next week, Carnell was all in. And by the time he made it through basic and Officer Candidate School, Carnell knew what he wanted — to be an infantry officer.

“I knew that I wanted to meet the enemies of my country on the field of battle,” he said. “That’s what the infantry does. They own that last 100 yards, and for me the American infantryman is the finest individual you will ever know.”

Carnell was deployed to central Europe in 2012 and began to refine his goals with an eye toward Special Forces, the Green Berets who are America’s specialists in unconventional warfare.

With Beverly set up in Charleston near friends and family, Ben drove back and forth to Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, N.C., for three years while training for Special Forces. His intense training included becoming qualified for combat diving. After graduation in 2016, he was deployed to the Middle East for combat operations.

‘A zombie movie’

In October 2018, just a month after his son Charlie was born, Carnell was sent to Afghanistan. Over the next couple of months, Carnell’s unit developed intelligence on a dense population of Islamic State-K fighters in a valley in Nangarhar province in the eastern part of the country. ISIS-K is a branch of the Islamic State of Iraq active in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

“The planning part was tough, by the nature of the target and what was there,” said Carnell, who was in charge of bringing in the combat power for the operation. “There were a lot of analysts saying that we shouldn’t go in because they were too densely dug in and the terrain was too much.”

One of Carnell’s superior officers had an answer.

“We’re descended from the boys who climbed Pointe du Hoc,” he said. “I think we can handle this.

On the night of April 3, 2019, the operation was a go. Carnell remembers preparing for battle and packing a hospital bag with his cellphone and a change of clothes in case he was wounded.

“I took some fluid through an IV, and thought it was so much like getting ready for a football game,” he said. “There’s a weird calm, and you are hanging out with your boys. Then it’s time to put your boots on and you are sitting out on the airfield, waiting for the birds to show up. It’s super quiet out there and I can’t even capture what it was like. It’s just the coolest feeling.”

The helicopters flew Carnell’s unit, made up of U.S. and Afghan soldiers, into the valley below the mountaintop village where the ISIS-K fighters were dug in. The Americans and Afghans made their way up the mountain and prepared to enter the village.

Maj. Jeffrey Wright, of the 24th Special Operations Wing, led a seven-man tactics team in the assault.

“In my 20-plus years of training and experience in the art of attacking and defending ground objectives, I have seen few more formidable defensive positions — or ones more daunting to attack,” he said in a statement to the Air Force News Service.

“I would have to reach for examples like Normandy, Iwo Jima or Hamburger Hill to appropriately convey the degree to which the enemy were prepared and ready for our assault.”

Carnell and his fellow soldiers were not deterred.

“I remember thinking, we are going to hit this village and clear this valley until they just don’t want anymore,” Carnell.

The ISIS-K fighters waited until Carnell and his men had entered the village before opening fire.

“They wanted us in there with them, which was very smart on their part,” he said. “We started taking contact from down the hill in front of us and we were in the hornet’s nest. … They were coming out of tunnels, and the only way to describe it is like a zombie movie. They are coming out of everywhere, out of tunnels and holes in the ground, and we are on top of them.”

Carnell was on top of one, as well. As he threw a grenade, he felt a sensation “like a hot hammer slamming into my leg.” He had been shot by an ISIS-K fighter right below him, so close the muzzle left a burn on his leg

“I knew it was a gunshot wound in my thigh, and I knew I didn’t have very long to take care of myself,” he said. “If he had been just a little more disciplined, I’d probably be dead.”

Carnell strapped a tourniquet around his own thigh, and with help began to hobble away from the front line.

“Then, the guy who shot me came running out,” he said. “I shot him, but before he died, he blew himself up.”

As Carnell lay on the gurney getting treatment, somebody wrapped gauze around his own finger and jammed it into Carnell’s wound to help stop the bleeding.

“It felt like he was elbow deep in my thigh,” he said. “I knew I needed something for the pain.”

The drug he was given produced an experience that still haunts him.

“Because of how bad the trip was, I wish I had not taken anything,” he said. “It’s a weird feeling, and I can still feel what it felt like … It’s not a lot of fun.”

As an Air Force gunship suppressed enemy fire for about an hour, Carnell and 14 other patients were hoisted onto three hovering helicopters and evacuated to safety. The crew of the AC-130U gunship, the Spooky 41, was awarded 14 medals last week, including two Distinguished Flying Crosses, for their actions in the assault.

Carnell was flown back to his base and taken to the hospital for an initial surgery.

“Then, they shoved a phone in my face and said, ‘You need to call your wife.’”

Aftermath

Beverly woke up at 4 a.m. in the family’s Mount Pleasant home to find Ben on the phone. She later saw she had missed three calls. Ben was still feeling the effects of the painkiller he was given.

“He sounded like he was on drugs,” she said. ”‘Don’t do drugs,’ he said.”

Throughout Ben’s deployments, Beverly had grown used to a routine — a call from Ben to say he’d be busy for a while, a few days of silence, and then a call to say he was OK.

“But I always sort of thought something like this would happen,” she said. “I knew once he started this, he wouldn’t be happy just hanging out. I always thought he’d either be terribly bored, or if he was doing something dangerous he’d be doing what he wanted to do.

“At first, he told me he wasn’t even coming home. He said, ‘Three weeks, and I’ll be back in the fight.’”

As the extent of Ben’s injuries became clear, it was apparent that wouldn’t happen. Doctors had to open up his knee to relieve pressure from compartment syndrome, likely saving his leg from amputation. He had two surgeries in Afghanistan and one in Germany before heading back to Fort Bragg.

His father drove to Fort Bragg to bring Ben home, his leg in a brace and his eyes still red from the IED explosion. He collapsed on the couch, pale and shivering and barely had time to hold his son before having to return to Fort Bragg the next day.

Ben, Beverly and Charlie moved to Fort Bragg as he rehabbed his injuries and pondered his future.

“My thought was, I’m getting healthy and getting back in the fight,” he said. “But then I felt like, can I keep doing this to my family? Are we going to have kids up there at Fort Bragg? And that started me thinking long and hard about getting out.”

Back in Charleston, Carnell returned to The Citadel to rehab with strength coach Donnell Boucher, who had joined the Bulldogs’ staff during Carnell’s playing career.

“In my opinion, Donnell’s program is one of the best,” Carnell said. “So I felt like that was what I needed, someone who knows me and can push me.”

Today, Carnell walks with just a hint of a limp. The Purple Heart and Bronze Star recipient wears a hardhat and works for Beech Construction. Charlie is 1½ years old and another baby is on the way this summer. Yet Ben still searches for deeper meaning in what he’s done and still can do.

“He’s wired differently,” says his father Marty. “He’s very much desperate to do what he’s supposed to be doing. I think that, right now, he recognizes how intense what he’s done is, and that it was something worthwhile. He definitely wants to make an impact in whatever he’s doing.”

Right now, that looks like hiring veterans on his job sites and making sure people understand their sacrifices.

“The Army spent a lot of money hooking me up with Harvard business school and talking about innovation and how to organize a staff and how to drive an enterprise,” he said. “And to be able to bring along vets and other soldiers in that would be great. We want to reinvigorate the skilled trades, which desperately needs it. And I’d like to get in the position to tackle things like the opioid epidemic.

“I’d like to get to the place where we are tackling real stuff.”

Until then, Ben Carnell will remember the soldiers he served with, the ones still abroad and the ones who never came home from those last 100 yards.

“You can’t imagine how wonderful these people are,” he said, “how smart and tough they are. So we need to appreciate that, and what freedom means. We are truly standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Prestigious Cincinnati and MacArthur awards presented to Citadel cadets

Prestigious Cincinnati and MacArthur awards presented to Citadel cadets Looking ahead to the major events of 2026-27

Looking ahead to the major events of 2026-27 Photos from campus: January in review

Photos from campus: January in review