As seen in The Post and Courier, by Stephen Hobbs

In March 1969, African American hospital workers had enough.

Underpaid and overworked, hundreds, mostly women, took their grievances to the streets of Charleston. They demanded better treatment, the rehiring of 12 co-workers fired by the Medical College Hospital, now the Medical University of South Carolina, and the recognition of the Local 1199B union.

Below are the words of strikers, community leaders and others remembering the more than 100 days of activism in Charleston that followed. The comments have been edited for length.

Kerry Taylor, professor of history at The Citadel, speaking at an April commemoration for the hospital strikers.

What we remember as a workers strike, a hospital workers’ strike, was really part of a broad hospital workers’ movement, and we should think of it as a broad movement. Of course, the women who initiated the strike, who led the strike, were at the center, but it really drew upon the support of wide segments of the African American community here in Charleston that included, of course, most immediately, their family members, but also faith leaders, students, other area low-wage workers and some elements of organized labor.

Outside of Charleston, of course, there was great support from elements of the labor movement and from the civil rights movement, most notably coming from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was kind of in the midst of its Poor People’s Campaign of 1968-1969. This was (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s) last crusade after the folks left Washington, D.C., in the summer of 1968 as part of the Resurrection City, they looked to Charleston as a continuation of the values and the goals of the Poor People’s Campaign. So really the eyes of the broader civil rights movement were looking to Charleston as kind of the next step in the future of the civil rights movement.

It’s also important to remember that the three months or so of the strike were part of a much longer struggle, that the organizing at the medical college began at least two years earlier. And was triggered in late-1967 by the firing of five African American workers who were subject to racist abuse at the hand of their supervisor. That’s really what triggered Ms. Mary Moultrie to begin talking to community leaders about how it is they could get those women’s jobs back and it was through that longer conversation that they contacted (Local 1199) in New York City, contacted (the Southern Christian Leadership Conference) and brought some much needed resources to bear in the hospital workers campaign. So it was built at the hospital, built on that long history of struggle going back to ’67. But, of course, it was built on a tradition of a freedom struggle tradition in Charleston that goes back to emancipation, if not many years before.

Louise Brown, one of 12 fired hospital workers at Medical College Hospital and a striker, speaking at a March event honoring the hospital workers’ strike.

We wanted better pay. We was tired of being worked so hard. All we wanted was a little bit of money for the hard work that we’d done. We didn’t get that. Instead, we got jailed. We got put in jail. We got whipped. We got beat. I got kicked out my house.

It was horrible. Racism is bad. But we cannot stop here. We got to fight on for what is right … What are we going do about it? We gonna stand still and let it happen to us all over again?

Let’s pass the torch. Let’s don’t leave it where it’s at. We started in ’69, we can finish in 2019.

We changed the system. Herbert Fielding got his job as representative, for the first black African American man since Reconstruction. He got his job. (James Clyburn) got his job. Mayor (Joe Riley) got his job. They hired more people in the city council because of the 12 women that stood up for what we know is right. We were not going to be defeated regardless of what happened.

Mary Moultrie, one of 12 fired hospital workers at Medical College Hospital and a strike leader, in a March 2009 interview for The Citadel Oral History Program.

I left Charleston for a few years, lived in New York. I returned in ’67 and got the job at the medical university hospital, and that’s when I became kind of active. I had worked at a hospital in New York, and when I got back here I found that things were completely different.

There were all kinds of grievances that people had. You know, it was not just being fired by students, but it was a lot of discrimination, was a lot of heavy workload, was nurses, they’re referring to blacks as monkey grunts, and all sorts of things that they had to either tolerate it or you’re fired. But we didn’t have no means of grieving, you know, if you had a grievance, you know, that was your business. You had no place to take it.

During that time, we had very few white nurse’s aides, but the few that were there didn’t get the heavy workloads that we got. And it was my understanding that they were paid differently. Nothing I could prove, you know, but I was told that they were making more than the $1.30 an hour that we were making. And they certainly didn’t work as hard as we did, so it was a difference.

Vera Smalls-Singleton, one of 12 fired hospital workers at Medical College Hospital and a striker, speaking at a March event honoring the hospital workers’ strike.

I was afraid. I was only 22 years old with two babies in the stroller. My husband at the time, the children’s father, he got laid off. I got fired. Rent was only $52 a month and we weren’t able to pay rent.

And I thank God we were the 12 that got fired. Because of us, that’s why the strike took place. Because everybody stayed out and support us. And that’s what we have to do today. We have to support one another.

I’ve never seen so many police, and National Guard and billy clubs. It was really, really a hard time in my life. I don’t know where I would have been because sometimes you have to go through some things to get to the next thing.

I am also blessed to be at the Medical University (of South Carolina), and retired. A lot didn’t do that. I retired from the Medical University with 31 years of service. And thanks be to God.

Rosetta Simmons, one of 12 fired hospital workers at Medical College Hospital and a striker, in a March 2009 interview for The Citadel Oral History Program.

Management needed to know that we are human beings, and we ought to be treated with dignity and respect. Money will come later, but just those things, being treated as human beings and being treated with dignity and with respect. And I think, when I think about all of what we went through, we got some respect, in a sense. Monies, a few pennies, came. But it was not overall the big thing. The big thing, as far as I was concerned, is that we were being treated as a human being, and before that, we weren’t.

When you are treated badly, and there’s a way where you can correct some of it, you stick with what you know, what you have, the help that’s been out here for you … I didn’t realize that some of the workers who were at Memorial Hospital were receiving the same kind of treatment over there, and this was how I started organizing at Charleston Memorial Hospital.

William “Bill” Saunders, among the earliest community advocates of the striking hospital workers, in a March 2009 interview for The Citadel Oral History Program.

So then they fired those 12, that really put us in a spot. Because we were not prepared to strike. And the (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) was here, and even the union was, but we were not prepared to strike. And the hospital, with the political wing, had hired a labor lawyer from Greenville. They decided if they fired those 12, which were the leaders, and then even if they strike they would get everybody back except for the people that they didn’t want back. That was the game plan. And they did, so they fired those, and they were assured that within, you know, 10 or 12 days, everything was going to be back to normal. But again, we also had our own plans.

It was the only thing except for Hurricane Hugo that I saw that brought the community together. I mean, we had the beauty shops doing people’s hair for free, and barber shops cutting for free. The ministers came together, white and black ministers that had never got together. The Catholic priests did so much, I mean, it stood up a lot, and there were some sisters and stuff … We understood, some of us that did some of the planning, we understood that the thing that drives everything, that especially drives Charleston, is the economics.

But it really brought some respect to people that never had respect before. I don’t know that the folks that was in charge would never believe that poor people could stop the city of Charleston.

Cecil Williams, an Orangeburg-based photographer who covered the hospital workers’ strike for Jet Magazine, in a May interview.

I was really, really jubilant when my picture was selected of (Coretta Scott King) to be on the front cover. It was one of the most happiest moments of my time.

The Charleston hospital workers’ strike in history was probably about the last of those great marches. And if that is so, from the perspective of a journalist like me, who saw the beginning in Clarendon County, that means that really the civil rights movement began in South Carolina (with the Briggs v. Elliott case) and ended in South Carolina with the Charleston hospital workers’ strike. So it was great to contribute to this historical milestone.

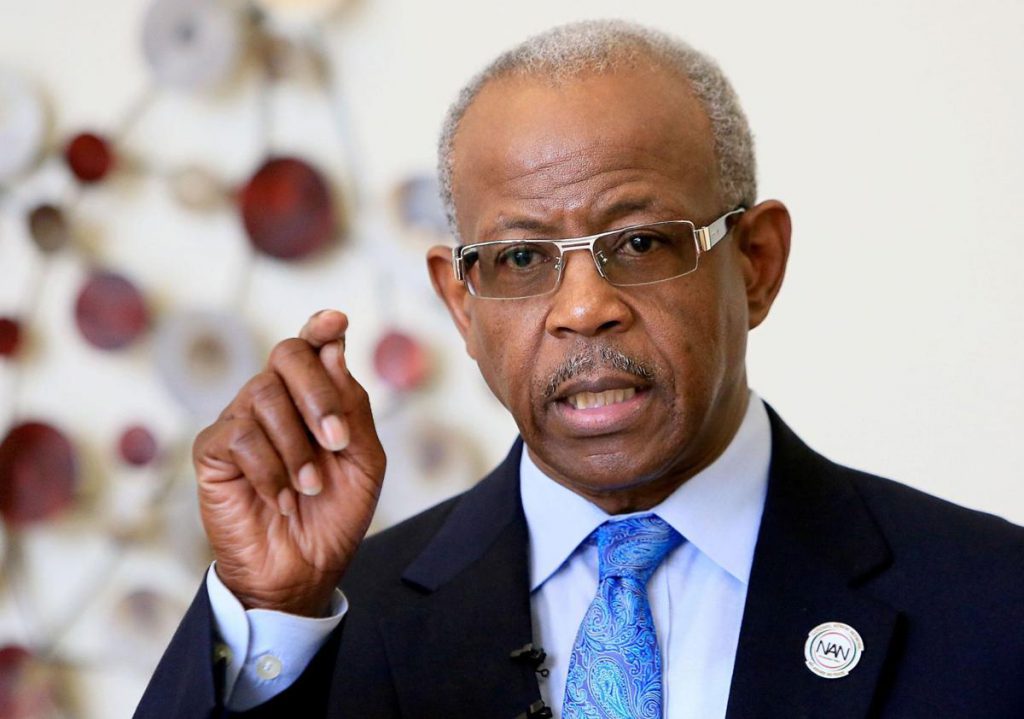

The Rev. Nelson Rivers, civil rights advocate and pastor at Charity Missionary Baptist Church in North Charleston, speaking at a March event honoring the hospital workers’ strike.

The memory kindles this longing in me, for where are the movement churches now? Because, on the front line of that march … it was pastors, fathers, leaders and even elected officials.

We remember the students who went to jail during the strike. Along with (the Rev. Ralph Abernathy). Trade unionists who stood with the hospital workers. The clergy and the church … sanitation workers and even the Georgetown steelworkers who organized their union for recognition months after the strike.

The Rev. William Barber II, civil rights advocate, speaking at a March event honoring the hospital workers’ strike.

It began as a dispute between employers and employees but it became, right here, a national, listen, an international debate.

In 100 days, they began to change. They boosted the pay. That’s the other side we’ve got to tell: they didn’t just protest, they won. They gained respect. They hastened the end of Jim Crow. Even many politicians today, that are active today, owe, whether they remember it or not, they owe their political lives to what these women did.

The Rev. John Reynolds, civil rights advocate and strike participant, speaking at a March event honoring the hospital workers’ strike.

One of my tasks here was to keep people from going downtown to shop. Because we put a boycott on. And if you remember, there were not that many malls back then. So you shopped downtown. The fine ladies would come downtown and my task was to keep them out of the store. Or if they went in the store to get them out of the store.

So I had a group of teenagers and we controlled King Street. We had cowbells and basketballs. And we went down the street dribbling basketballs and ringing cowbells. And we were going in department stores and these ladies would look at us and we’d just say, “We’re having a good time. There’s no time to shop because we about to party.”

It was important to the whole community that that movement took place. Because out of that movement you have better health care now in Charleston.

Out of what they did we have better schools. Because of what they did we have more black professional medical folks. Because of the sacrifice that they made.

Andrew Young, civil rights activist, hospital strike participant and former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, in a speech at a hospital strike commemoration event in May.

I felt an obligation to kind of carry on the things that (Martin Luther King Jr.) stood for and the things that he gave his life for. So we came here with the hospital workers because we had been with him with the sanitation workers. And he made a particular point of not wanting to be in New York or Washington at the time of his death. I think he knew his days were numbered.

I think we came here because we felt we were following in his footsteps. But I wasn’t trying to win a strike. I was trying to get a hospital going again. And I read in the Time magazine that (hospital President William McCord) was the son of Presbyterian missionaries in South Africa. And I said, “He can’t be all bad.”

Joe Riley, Charleston mayor from 1975 to 2016 and state legislator during the strike, in an interview and at a hospital strike commemoration event in May.

Interview:

I think the strike gave momentum and encouragement and reinforcement for the search for racial justice and civil rights in the community. I think when it was over African Americans felt empowered.

During the time, the Civil Rights Act had been passed, the Voting Rights Act had been passed, and both added substantial momentum to racial progress and civil rights here. So I think that the community was different after that. And I think the African American leadership, as I said, was more empowered, and had reason to be more confident and more determined.

Photos from campus: February in review

Photos from campus: February in review The Citadel’s presidential search committee announces four finalists

The Citadel’s presidential search committee announces four finalists Photos from campus: January in review

Photos from campus: January in review