As seen in Charleston CEO, by Melissa Graves

Members of the intelligence community are obsessed with critical thinking because their assessments have real-life consequences. As I write this column, analysts are pondering such critical issues as North Korea and Iran’s intentions with their respective nuclear programs, China’s strategy in the South China Sea, and the likelihood of U.S. military success in Afghanistan. These questions carry life or death, peacetime or wartime, consequences.

Contributions of leaders within the intelligence analytical community have helped sharpen analysts’ thinking so that they can make the best assessments possible. One such expert, Richards J. Heuer, Jr., wrote Psychology of Intelligence, which gained international prominence among intelligence practitioners following the events of 9/11. A former CIA analyst, Heuer’s work is one of the earliest pieces to examine how analysts think. His truths are as salient as ever, both to intelligence analysts and to those in other fields who simply want to think better.

To think more critically, Heuer contends that people must first reckon with their biases. Before people can improve their thinking, they have to understand the mental potholes that impede good decision making. Heuer’s insights can be summarized as follows:

We tend to perceive what we expect to perceive. For Heuer, perception is formed primarily from expectations, not reality. In other words, what we want to see is likely what we’ll get. It’s possible that we can misperceive a situation from the very beginning, making it impossible to ever think about things clearly. It can be as simple as looking at a challenging situation, feeling defeated from the start. If we expect the worst, we’re likely to find it. It’s important to remember that our perceived reality is distorted based upon our own attitudes.

Mind-sets tend to be quick to form but resistant to change. We know the old adage about first impressions, and it turns out that the myth is true. Heuer explains that when we are introduced to new information, we have a short window of time in which we make up our minds. Once our minds are made up, we’re likely to throw down our anchors, call it a day, and resist altering our judgment. So, first impressions matter, and it’s important that we understand how quick we are to form them based upon very little information.

New information is assimilated to existing images. Similar to first impressions, Heuer contends that once we make up our minds, any new information is likely to support our mindset, even if that new information suggests that our mindset is wrong. In other words, once we make up our minds, it’s unlikely that we’ll objectively assess new evidence. Rather, we’ll see the new evidence in light of our old beliefs, and file the new information away accordingly.

Heuer’s book remains a staple among intelligence analysts because it identifies areas in which our ability to think well is hindered by our own biases. Great analysts will never be satisfied with their ability to think through issues; their constant refining of past judgments is what helps them improve their analysis. The same can be said for great thinkers everywhere, in every discipline. Being aware of the mental shortcomings Heuer identified, however, can help us slow down, reassess what we really know, and think about things a little better.

Melissa Graves, Ph.D., is a professor in The Citadel Department of Intelligence and Security Studies and an attorney. She teaches undergraduate and graduate level courses in intelligence analysis, exploring ethical and legal issues. Graves’ research interest is U.S. presidency relationships to the intelligence community, and intelligence analysis. She has published numerous articles, is author of a chapter on FBI historiography in Intelligence Studies in Britain and the U.S., and a co-author of Introduction to Intelligence Studies, as well as co-author of an upcoming release, Historical Dictionary of the FBI.

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit

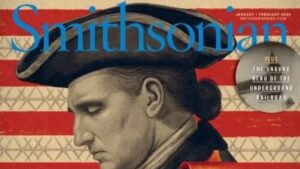

Moore Art Gallery opens “All Hands on Deck” WWII naval photography exhibit Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine

Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine Citadel professor to serve as next Inspector General for the U.S. Department of Defense

Citadel professor to serve as next Inspector General for the U.S. Department of Defense