As seen in The Summerville Journal Scene, by Jenna-Ley Harrison

Friday was a day of celebration, reflection and looking ahead to the exciting new future awaiting the Lowcountry’s only seminary.

Alumni, faculty and religious leaders from Cummins Memorial Theological Seminary in Summerville gathered with community members inside the historic building on South Main Street to not only announce the facility’s success in matching a $50,000 anonymous donation but also praise past leaders and ongoing renovations.

The event also centered on the seminary’s ties to local black history.

“This is a great day…and this is just the beginning of what God will do,” said Rev. Dr. Julius Barnes, president and dean of Cummins.

Using the analogy of an eternal fire, Barnes championed the seminary’s ecumenical work and Christian service in the Summerville area for more than a century—though the school was established “without walls” at a much earlier date.

“This spark must be passed on,” Barnes said. “The flame will continue to burn; the fire will not go out.”

It was a local couple’s anonymous $50,000 donation that Barnes said “sparked the flame.” The pair approached him in April, offering the money if officials could meet the challenge of matching it. Religious leaders exceeded the amount, raising $52,000.

Barnes said he looks forward to seeing the money further the institute’s goal of educating men and women to affect the greater Charleston area and beyond.

“Those who walk the halls of Cummins Seminary, those who sit in the classrooms, those who learn will be able to touch lives,” he said. “We can change the tri-county area; we can change the state of South Carolina; we can change this nation through the power of the Gospel.”

According to Cummins professor of Greek and New Testament classes John G. Panagiotou—also liaison to the school’s president—half of the $102,000 will be used for the current accreditation process. The seminary is hoping to gain national accreditation by 2020 and already has state accreditation, a vision from Barnes, according to Pastor Tory Liferidge, development consultant for Cummins.

“In this season…we have really worked to revitalize this institution,” he said.

Liferidge said it was in 2013 when Barnes first noted his desire for Cummins and outlined his goals for it.

“He had a very robust vision of what this seminary could become again and even surpass its former greatness,” Liferidge said. “And so we began a journey.”

The money’s remaining half will help establish a seminary endowment “to create a firm financial foundation for the seminary in the future generations,” according to Panagiotou. He said community members are invited to donate to the endowment.

Officials said no funds will go to current renovations to classrooms and that the Reformed Episcopal Diocese of the Southeast has taken out a loan for the renovations, which Panagiotou estimated would cost about $350,000 and include updating technology.

“This is a grand, old lady who needs a lot of love and care,” he said of Cummins.

During Friday’s ceremony, attendees also looked back on the seminary’s humble beginnings, the historic leaders who shaped it and significance of it all to black history.

Historical significance

A former Confederate Army colonel, Peter F. Stevens, founded Bishop Cummins Training School as a seminary for blacks in 1876. Rev. Frank Crawford Ferguson, a former slave, assisted Stevens in the effort. The school was named after Bishop George David Cummins, who three years earlier had founded the Reformed Episcopal Church.

“We have several beginnings within the decade of the 1870s,” said Canon J. Ronald Moock, academic dean for Cummins.

Moock detailed the facility’s history for the crowd and told of Stevens’ initial connection to the Palmetto State. Born in Florida, his mother moved him and his siblings to Pendleton, South Carolina, during the time of Seminole Indian conflict in the Sunshine State.

Stevens was a “man of courage; a man of leadership” and “a man of love,” according to Barnes.

Stevens is also famous for his role in firing the first shots of the Civil War in the Charleston Harbor. The governor at the time had ordered him, with a crew of Citadel cadets, to fend off Union supply ships to Fort Sumter in December 1860, according to historians. The cadets fired three times on the Union ship, Star of the West, prompting the vessel to turn before reaching the fort, Moock said.

At the time Stevens boasted the rank of major and was superintendent—or president—of the military college, where he also had attended and graduated top of his class, Moock said. But not long after the Civil War, Stevens decided to forge a new, religious path; in 1861 he resigned from his educational role and became ordained through the Protestant Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina, seeking to continue his work educating slaves.

“I don’t know what happened to him, but the Lord got hold of him, changed him from the military into the ministry,” Moock said. “He had already been involved in helping his black constituents, and now those black constituents within his parishes he seeks to train and educate.”

Stevens’ war efforts are not forgotten. A mural of him, with his sword drawn and surrounded by his cadets in the harbor, hangs inside The Citadel.

Despite the adversity he faced for his new mission with minorities, Stevens persevered.

“He was persecuted for it; he was ridiculed for it,” Moock said.

The diocese even refused to ordain the freed, black pupils Stevens educated as part of his effort to start black area parishes.

But the tide began to turn in 1874 when Moock said a missionary with the Reformed Episcopal Church—willing to accept freed, black men—responded to a request to meet with Stevens in Charleston. Moock said the evangelist reported good news to church headquarters, prompting Reformed Episcopal Bishop Cummins to journey to the area the next year.

During his visit, Cummins made history, ordaining three black men and organizing the area’s first four black parishes. Because of “his leadership and love for the people here,” Stevens was also appointed superintendent of the new religious operation—“the beginning of what is now our Diocese of the Southeast,” Moock said. The diocese’s headquarters is currently housed at Cummins Seminary.

In 1879 Stevens becomes the first bishop of the young diocese.

During this time, Bishop Cummins Training School develops, initially as a “traveling” seminary—one without a building. It centered on Stevens’ location and “moved around like the medieval seminaries,” Moock said.

For a time he resided in Orangeburg as a math professor at what is now S.C. State University. Students attended both seminary and college classes while also serving their Sunday parishes.

“Always working for the Lord in their various capacities,” Moock said.

Stevens died in 1910—his body buried in Magnolia cemetery. Bishop Arthur Pengelley became his successor and namesake for the current Pengelley Chapel—known in its earlier days as St. Paul’s Reformed Episcopal Church. The chapel is situated behind the seminary along East Sixth South Street, where it’s been since 1912, said church officials.

Summerville was chosen for its train stop and centralization to parishes in Charleston and Berkeley counties. Church historians said the chapel, built in the 1880s, was also formerly a site for educating underprivileged white and Native American students before the public school system was established. Children also received healthcare there.

During those days, the chapel was known as St. Barnabas Mission School, under the ownership of St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Summerville. But the Reformed Episcopal Church snatched up the abandoned chapel in 1946, Moock said.

It was in 1924 the seminary gained its first permanent site in the town’s Brownsville community. It was known as Bishop Cummins Memorial Training School then, Moocks said. The state officially chartered the school under its current name in 1939.

A few years later the seminary moved to the site of Summerville’s former Bank of America, at the southwest corner of North Main and West Fourth North streets. At the time the building operated as a hospital for the area’s black population.

Dr. John Alston, for whom Alston Middle and Alston-Bailey Elementary is named, operated the clinic until it closed in late 1930s. When the clinic moved to a black patient wing inside the new Dorchester County hospital—currently the site of the county’s Human Services Building—the empty property became available for the seminary to purchase, said church leaders.

In 1966 the Reformed Episcopal Church welcomed its first black bishop, Sanco King Rembert.

In 1980 the seminary moved to its current site on South Main Street, the former home of Pinewood Preparatory School, which moved to Knightsville, Moock said.

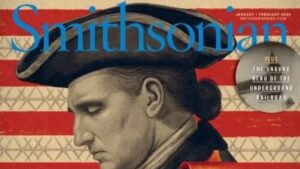

Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine

Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine Employee of The Citadel DoD Cyber Institute selected to be deputy commanding general of U.S. Army’s Cyber Center of Excellence

Employee of The Citadel DoD Cyber Institute selected to be deputy commanding general of U.S. Army’s Cyber Center of Excellence Citadel upperclassmen get hands-on leadership training at Parris Island

Citadel upperclassmen get hands-on leadership training at Parris Island