As seen in The Post and Courier, by David Wren

Oysters normally aren’t associated with large-scale economic development initiatives, but the staple of backyard roasts is playing a vital role in a pair of Charleston projects.

The Citadel Foundation and the city of Charleston are teaming up to build oyster reefs along the western edge of the Ashley River to serve as environmental mitigation for construction activities on the peninsula that required permitting from the Army Corps of Engineers.

For the city, the reef program helped obtain permits for the next phase of a deep-tunnel drainage system along the Septima P. Clark Parkway, commonly referred to as the Crosstown. The Citadel Foundation — a nonprofit that raises money for the school — will use the reefs as mitigation for dredging a channel to the Ashley River and construction of a pier and boating center for students.

Entities are often required to mitigate for impacts to wetlands due to construction, and that typically involves purchasing land in existing mitigation banks in other parts of the state. The oyster reef project is unusual, with neither the city nor The Citadel Foundation participating in such a program before.

The collaboration is also unique, with two entities agreeing to split the mitigation costs for separate and unrelated projects.

“What we said was, if we’re each doing a mitigation project, let’s do it together and save the money on the overhead and get some economy of scale,” said Matthew Fountain, the city’s stormwater director. “It’s a good way to cost share.”

The two sides had 14,000 bushels of shucked oyster shells brought to this area from the Gulf Coast because “there’s literally not that quantity available for purchase in South Carolina,” Fountain said.

The shells have been drying out at the Port of Charleston’s Veterans Terminal for the past six month. In the coming weeks, a contractor will move the shells by barge from the terminal along the Cooper River to the Ashley River reef sites.

The shells will be installed across the river from Brittlebank Park and The Citadel campus by the end of August, creating reefs designed so new, live oysters will attach to the shells. The new oysters help filter the river water, removing pollutants like nitrogen as they search for nutrients. As the reefs grow, they will help to stabilize the shoreline and marsh while serving as a habitat for fish, shrimp, crabs and other animals.

The state’s Department of Natural Resources will monitor the reefs’ health over a three-year period, at which point they will be mature enough to flourish on their own.

The reefs will help mitigate the city’s $52 million fourth phase of drainage improvements to the busy six-lane parkway. The project includes a pump station that will move stormwater from tunnels 140 feet underground to outfalls that empty into the Ashley River.

Edison, N.J.-based Conti Enterprises will do the work, which is expected to be finished in 2022.

The Citadel’s new Swain Boating Center will replace an older boathouse, built nearly a century ago, that had fallen into disrepair and was torn down. A new dock has been built and the channel has been dredged. The school recently awarded a nearly $1.2 million contract to Branks General Contractors for construction of a 1,200-square-foot open-air pavilion and separate dock house.

Dr. Christopher Swain, a Citadel alumnus, and his wife, Debbie, donated the money to rebuild the school’s boating center, as well as an endowment to maintain it.

“This essentially brings that facility back to life as a quality of life enhancement for our cadets, students, faculty, staff and alumni,” said John Dorrian, vice president for communications and marketing at The Citadel.

A surge of oyster shell recycling programs have emerged in coastal regions in recent years, such as the South Carolina Oyster Restoration and Enhancement program run by the Department of Natural Resources.

A study by the Harte Research Institute in Corpus Christi, Texas, shows 80 percent of oyster habitats have been destroyed by over-harvesting and pollution during the past century.

“When you harvest an oyster, essentially you harvest its habitat right alongside it,” Dr. Jennifer Pollack, chair of the institute, said in a statement.

Fountain said the mitigation project is a positive move on several fronts and something the city might try again.

“It’s a nice project because you provide a filter feeder, which helps water quality, you provide oysters, which are good for commerce and it helps marsh revitalization, which can slow storm surge,” he said.

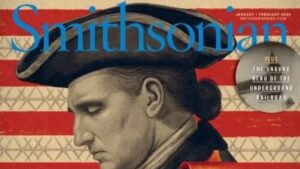

Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine

Citadel professor published in the Smithsonian Magazine Employee of The Citadel DoD Cyber Institute selected to be deputy commanding general of U.S. Army’s Cyber Center of Excellence

Employee of The Citadel DoD Cyber Institute selected to be deputy commanding general of U.S. Army’s Cyber Center of Excellence Citadel upperclassmen get hands-on leadership training at Parris Island

Citadel upperclassmen get hands-on leadership training at Parris Island